Debating Religion

This is a collection of five articles that address religious controversies in South India, from roughly the twelfth to the nineteenth centuries.

Articles

In this article, I explore the processes through which Tamil-based Śaivism came to be conceptually equated with the maintenance of a vegetarian diet, a development reflected in the modern Tamil word caivam (Skt. śaiva), which in colloquial speech primarily signifies lacto-vegetarian cuisine. I contend that although Tamil Śaiva literary sources have long articulated the normativity of vegetarianism, the conflation of Śaiva praxis with plant-based dietary habits likely dates to the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Such, at least, is the picture that emerges from a consideration of the Kolaimaṟuttal (Rejecting Killing), a brief polemic against animal slaughter likely composed in the then-frontier region of what is now the suburbs of Coimbatore, which emphasizes dietary nonviolence as the quintessential Śaiva virtue and the principal basis for demarcating Śaivism from other religions. A close reading of this hitherto unstudied text suggests that early modern Tamil Śaiva food discourse transformed, at least in part, in response to the emergence of new notions of “self” and “other” in this period, which prompted a corresponding need to rethink the contour and configuration of community boundaries.

10.82239/2834-3875.2024.2.1

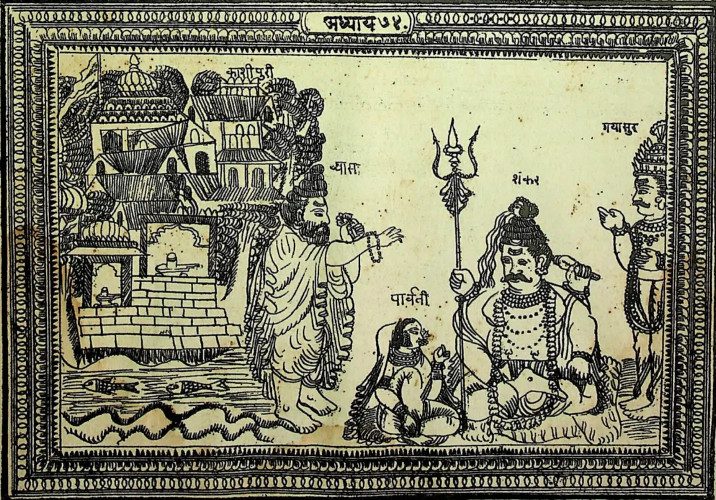

This paper examines the textual and juridical history of Vyāsantōḷ, a once-popular Vīraśaiva procession in which the severed arm of Vyāsa — the storied author of the Mahābhārata — was paraded through villages and cities throughout the Deccan. As a sacred figure for some, Vyāsa’s desecration provoked ire and occasional violence until 1945, when the Bombay High Court outlawed the practice. This paper examines Vyāsantōḷ across three turning points. The first is a polemical praise-poem (stōtra) titled Praising Vyāsa, Condemning the Apostates (Pāṣaṇḍakhaṇḍanavyāsastōtra) written by Vādirāja Tīrtha (ca. 1550–1610), a popular intellectual and proselyte of Madhva’s realist Vedānta and the first known writer to weigh in on the question of Vyāsa’s arm. The second is a genealogy of Vyāsantōḷ in the Mahābhārata, Purāṇas, and Śaiva didactic writings. And the third is the circuitous course that Vyāsantōḷ cut through courts in British India. Collectively, these turning points provide not only a provisional genealogy of a religious controversy; they also remind us that figures like Vyāsa belong not to epic antiquity, but to a present in which gods and epic heroes are refigured (or disfigured) according to the interests of historical communities.

10.82239/2834-3875.2024.2.2

The vacanas, short devotional poems in the Kannada language that started to be composed in the twelfth century, are central for the modern identity of the “Vīraśaiva” or “Liṅgāyat” religious tradition and are also popular among the Kannada-speaking public and, through translations, global audience. But there is an ongoing interpretive controversy of what the vacanas are “really” about, and this partly rests on the “authenticity” of the poems themselves. While most uncritically attribute the vacanas we have at hand today to the twelfth century, some reject this attribution by pointing to the vacanas’ complex history of transmission and dissemination over roughly eight centuries, and specifically to the fact that written collections of vacanas only started to appear during the fifteenth century, three hundred years after their purported composition. This article adds nuance to the above controversy by tracing quotations of vacanas in a written hagiographical text that was created around the turn of the twelfth century. While disproving the claim that no written evidence for vacanas exists before the fifteenth century, the article also complicates assumptions about their content and other textual features in the early period by pointing to the relative marginality of the vacanas in the early hagiographical material, the absence of the term “vacana” and a concomitant appreciation of their outstanding poetic features in it. Lastly, the article suggests several options for explaining the difference in how the vacanas were understood in the early period and today.

10.82239/2834-3875.2024.2.3

One of the earliest authors of Vīraśaiva vernacular literature, Pālkuriki Somanātha, author of the thirteenth-century Basavapurāṇamu, crafts a hagiographical vision for his emerging community that relies heavily on narrative accounts of violence against religious others, particularly Buddhists and Jains. This article revisits the question of narrative violence in Śaiva and Vīraśaiva literature by way of an unstudied episode of the Telugu Exploits of Paṇḍitārādhya (Paṇḍitārādhyacaritramu). Through a close reading of Somanātha’s account of the murder of a Buddhist monk, I argue that the upsurge of narrative violence attested in Somanātha’s works and adjacent Śaiva vernacular literature must be read in the context of contemporary epigraphical and multilingual prescriptive literature. I suggest that discursive commonalities between these genres—in particular, the use of the term śivadrōha(mbu), “treachery against Śiva”—shed new light on the relationship between religion, law, and violence at the end of the Śaiva Age in south India.

10.82239/2834-3875.2024.2.5

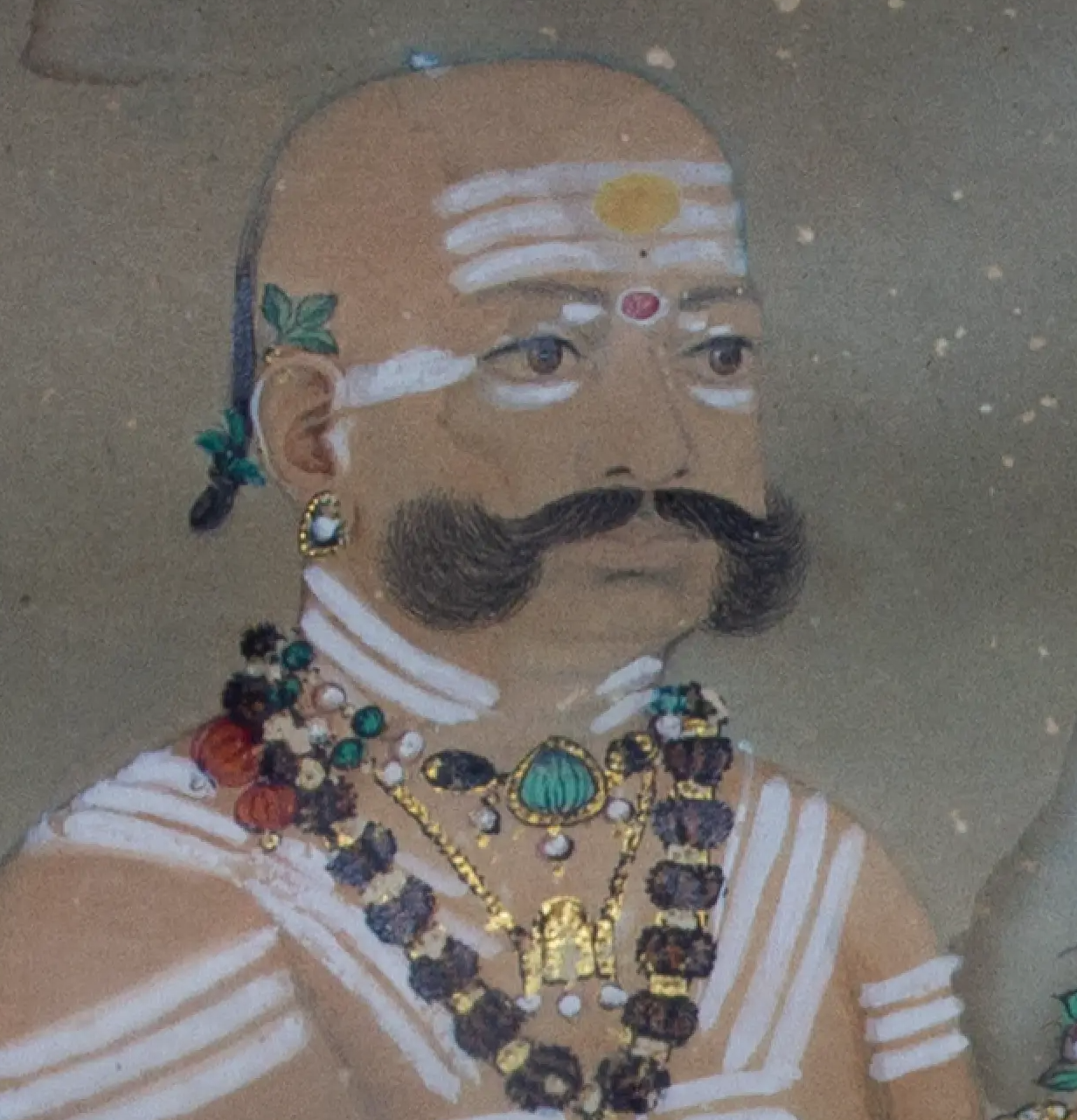

This paper investigates the historical construction and political positioning of Liṅgāyat identity within the context of the Mysore court, emphasizing the influence of political expediency in shaping religious boundaries. Through an analysis of two key narratives about rebellion—one set in the seventeenth century and the other in the nineteenth—the paper explores how Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyats navigated the shifting allegiances and socio-political structures of colonial Mysore. This study argues that Liṅgāyat identity was not solely a product of theological differentiation but was significantly shaped by external political forces. This analysis highlights the intricate relationship between religious identity, state power, and historical memory, offering insights into the broader mechanisms by which religious communities are situated within political frameworks.

10.82239/2834-3875.2024.2.4