Introduction

Recently, Liṅgāyatism, and more precisely its place in broader classifications of religion in India, has once again become the subject of controversy in Indian legal and public discourse: are Liṅgāyats Hindus? At stake in this controversy are both the Indian Constitution’s definition of religion(s) and an individual’s and/or community’s agency in determining their own religious identity. Some Liṅgāyats had been claiming for decades that they were not Hindus, but it was up to the government to recognize those claims. The conversation over Liṅgāyat religious identity came to a flash point on March 19, 2018, when in a landmark decision, the Congress-led Karnataka Government and its Chief Minister Siddaramaiah decided to grant Liṅgāyatism, whose followers make up 17% of the state’s population, the designation of “minority religion” (Times of India, March 20, 2018). With this declaration, the state officially marked a distinction between the broader Hindu traditions and the Kannadiga tradition that self-identifies as a separate, non-Hindu religion and traces its philosophy to the bhakti poet Basava of the twelfth century. Many aspects of the political intention and potential impact of the state government’s decision, including its implications for Indian constitutional hermeneutics and Indian jurisprudence and legislation, lie outside the scope of this essay. In this article, I wish, instead, to use this monumental decision as an opportunity to think about religious identity and the agency through which a group or tradition has the power to demarcate its own boundaries within the broader landscape of religions and religious traditions, particularly those in India. I am interested in the inherently political process of deciding who is “in” and who is “out,” who is part of the group and who is, for whatever reason, pushed outside its confines, and, finally, how the decision-making process inevitably resides beyond the agency of the group whose (religious) identity is in question. Indeed, in the days following the Karnataka government’s decision, many implied, suggested, or outright accused the reigning Congress government’s decision of pandering to the Liṅgāyat community in an attempt to mobilize its members, approximately 10 million people, in the upcoming statewide elections, and Congress has, likewise, accused the BJP of turning a matter of social and religious identity into an opportunity to sow political discord.

I begin this article with the recent debate described above as a starting point to highlight the ongoing importance of Liṅgāyat community within Kannadiga politics and to highlight how the negotiation of Liṅgāyat identity is subject to political intervention. In this article, I examine two narratives of rebellions, set in the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries and written in the nineteenth century, that demonstrate how political positionality became mapped onto the modern religious identity of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyats—two terms that have their own histories but are interchanged in the Kannada sources that I discussed below and I, therefore, use both terms simultaneously to describe the group/tradition. I argue that histories of the Mysore court, particularly stories of these two revolts written in the nineteenth century, were vehicles for political positioning of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyatism through negotiation of its acceptability as courtly religious tradition of the Mysore. The political inclusion or exclusion has continued to be a political touch point in the Kannada-speaking south. More broadly, I am interested the ways that different agents mobilize religious identity for political expediency, and, particularly, the pragmatism that determined Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyats’ ritual participation in the Mysore court. That is to say, the place of Liṅgāyatism within the broader religious landscape was determined by political concerns relative to where the Liṅgāyat community fit into a political agenda, long before contemporary contentions over the place of religion and religious groups within democratic Indian politics.

I ground my discussion in narratives surrounding two rebellions recorded in nineteenth-century Karnataka, particularly in the kingdom of Mysore that lies in the southern portion of the modern Indian state of Karnataka. By this time, Liṅgāyatism was well established and had matured as both a religious tradition (including established temples, unique rituals, powerful maṭhas, and institutional hierarchies) and as a caste identity. To draw out the precarious history of Liṅgāyatism in the context of burgeoning modernity, I focus on two cases of rebellion against the Mysore court by communities of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyats in which the tradition and its leaders were the focus of political contention. One of these cases was set in the late seventeenth century, one in the early nineteenth century, but both were written about in the nineteenth century. Through these case studies, I hope to show how the Liṅgāyat religious beliefs and practices had little bearing upon their acceptance into the fold of religious traditions of the Mysore court or its political favor. Instead, their status as insiders or outsiders was prescribed and enacted upon them as a measure of political expediency.

The case of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyatism in nineteenth-century histories allows us the opportunity to examine the negotiations of identities and how blurry lines of identity, practice, and belief come to form rigid boundaries that separate one group from the next, a process that seems to be as inherent to the category of religion/religions as any other practice, belief, or spiritual pursuit. I suggest, much like Orsi (2006), Chidester (1996), and Boyarin (2004), that rigid distinctions between religious traditions are not natural but imposed from the outside as a means to control, isolate, and/or demean the other. Likewise, in the case of early modern and early colonial Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyatism, the inclusion and exclusion of the tradition from positions within the Mysore court was imposed by the politically strong upon the politically vulnerable, and whether they were “in” or “out” was not simply a theological parting of ways. Instead, minority religious identity was decided by the political elite as they worked to consolidate their own political identities.

Cikkadēvarāj and Religion in the Mysore Court in Seventeenth-Century Sources

In the vacuum of political power in the Deccan created by the decline of the Adil Shahi Sultanate, Cikkadēvarāja ascended the throne of Mysore in 1673 ce, unthreatened by the Mysore kingdom’s rivals in Bijapur. Cikkadēvarāja strengthened diplomatic relations with the Mughal emperor Alamgir (Aurangzeb) and his general Qasim Khān. Simultaneously, Cikkadēvarāja defended his kingdom against repeated incursions by the Maratha rulers, including Śivajī and his son Śambhājī. Cikkadēvarāja not only repelled the Marathas but expanded the Mysore territories (Cikkadēvarāya Binnapam vv. 4–5; Wadayar 1949: 1–5; REC My. 99). For his efforts, Cikkadēvarāja’s royal chronicler and court poet Tirumalārya bestowed upon him the epithet of “Unequalled Hero” (apratima-vīra). Cikkadēvarāja ruled for thirty-two years, longer than any other Mysore king, enjoying a period of imperial control like no other Woḍeyar ruler before or after. While his rule is generally described as one of great peace and stability, the territory of Mysore was under continual onslaught from the south by the newly established Maratha Nāyakas of Madurai and from the north by the Keḷadi rājas of Ikkēri, to whom I will return.

Though the royal histories of the time and his many royal eulogies focused on his military exploits, Cikkadēvarāja was also lauded for the cementing Śrī Vaiṣṇavism as the official tradition of the Mysore rulers during his reign. Indeed, his first major act of patronage in 1674 was the construction of a temple at Trikadamba Nagarī in which he established an image of the principal deity Paravāsudēva, his consort Kamalavallī, and two courtesans (nācayār) (REC My. 99). The temple was also given implements for conducting Rāmānuja pūjā in honor of the Śrī Vaiṣṇava saint in order to secure Cikkadēvarāja’s father Doḍḍadēvarāja’s perpetual state of bliss in heaven. The foundation inscription that commemorates the establishment of this temple was written by the court poet Tirumalārya, who would eventually become the king’s prime minister, and refers to Cikkadēvarāja as the “Stabilizer of Śrī Vaiṣṇava doctrine” (śrīvaiṣṇava mata pratiṣṭhāpaka; REC My. 99, line 432–433). In addition to this first donative record, the king from early in his reign showed interest in and patronized works by Śrī Vaiṣṇava poets and philosophers. Prominent among them was Cikkōpādhyāya, author of the Divya Sūri Caritrē (a Kannada translation of the Tamil poetry of the twelve Āḻvārs and a collection of māhātmyas or “glorifications” of popular Śrī Vaiṣṇava pilgrimage sites). These work stress the importance of Śrī Vaiṣṇava tenets in the Woḍeyar political administration and affirm the influence of the tradition in the governance of the region under Cikkadēvarāja. It was not until 1678, however, that Cikkadēvarāja was formally initiated into the religion. After this point he became a staunch and vocal proponent of the Śrī Vaiṣṇava tradition in Mysore and regularly received the epithet of the “Stabilizer of Śrī Vaiṣṇava doctrine” in the region.

Cikkadēvarāj and Religion in the Mysore Court in Nineteenth-Century Sources

One hundred and fifty years later, however, a different vision of Cikkadēvarāja’s court emerged in colonial-era scholarship. These sources maintain that early in his reign, Cikkadēvarāja’s court had space for a plurality of religious and sectarian traditions. In the early 1800s, in his Rājāvaḷi Kathāsāra, the Jain poet and historian Dēvacandra writes in great detail about Cikkadēvarāja’s training with three gurus from three different religious traditions: Tirumalārya (Śrī Vaiṣṇava), Ṣaḍakṣariya (Vīraśaiva), and Viśālākṣa (Jain, Saṇṇayya 1988: 341, 347). Dēvacandra writes that they each had a profound impact on his religious practice and in the administration of his kingdom. Dēvacandra worked with the Mysore Survey under the leadership of Colin Mackenzie, and it was for the Survey that he wrote his account, receiving a commission of 25 rupees from the surveyor in 1804 (Sastri 1941). According to Dēvacandra, at Cikkadēvarāja’s coronation, he selected the Jain Viśālākṣa (also called Yaḷandūra Paṇḍita and Yelandur Pundit) as his prime minister. According to Wilks (1869 [1810]: 124), this led many to believe that the king intended to be initiated as a Jain. Several scholars have also maintained that Cikkadēvarāja was a practicing jaṅgama, a wandering Vīraśaiva priest (Śastri 1920: 47; Rice 1897: 2461). C. Hayavadana Rao, a colonial historian of the Mysore court, followed Wilks in arguing that Cikkadēvarāja remained a devout “jangam” (1943: 482) from the time of his coronation through the early years as king. Of note in each of these colonial-era sources is that Śrī Vaiṣṇava, Vīraśaiva, and Jain are all treated as distinct traditions. There is no implication that Śrī Vaiṣṇavism and Vīraśaivism are any closer to one another as “Hindu” traditions than they are to Jainism, but they are all shown as equally competing for recognition and supremacy in Cikkadēvarāja’s court. Moreover, it appears that while they jockeyed for position and patronage—and contrary to broader theological and ideological positioning—these traditions were not portrayed to be mutually exclusive with the king simultaneously participating in rituals associated with all three traditions.

These same sources point to the civil strife of 1686 as an important turning point for the sectarian affiliation of the Woḍeyar court. After losing the city of Madurai and paying a handsome ransom for peace earlier in the same year, the Mysore kingdom was weakened and its coffers dwindling. Cikkadēvarāja therefore worked to reconcile the state’s financial burden by increasing tax revenues in his domains, especially some of his newly acquired domains in the north. The exact amount that was levied on the yield is not known for certain. While many sources claim that the king raised the taxes on the land up to one-third of the produce, twice as much as the one-sixth prescribed in most traditional legal texts (e.g., Manu Smr̥ti, Wilks 1869 [1810]: 124–128), others claim that Cikkadēvarāja simply started enforcing tax collection (Rice 1897: 2462). Regardless of the amount, provincial cultivators resented the increased economic burden. These cultivators included residents of the erstwhile Keḷadi kingdom of Ikkēri when Cikkadēvarāja’s army defeated Basappa Nāyaka in 1682. The Mysore and Keḷadi kingdoms had been involved in ongoing conflicts throughout the seventeenth century, and the Mysore armies had regularly attacked these lands for decades. The kingdom was annexed by Cikkadēvarāja in 1682, but after the tax reforms were put into place in 1686, a large part of the territory reportedly revolted against Cikkadēvarāja. The ruler and many of the subjects of the Ikkēri kingdom had been Vīraśaiva-Līngāyatas, and the network of jaṅgamas and their vast system of maṭhas throughout the region was allegedly instrumental in organizing the revolt. It was accordingly the Vīraśaiva-Līngāyata religion against which the state retaliated. Ironically, if we take Wilks’s account at its word, it was the effective organization of the Vīraśaiva-Līngāyatas that led them to become peripheral in the royal networks of religious practice and patronage.

Due to a dearth of sources, it is difficult to accurately reconstruct how the events of this rebellion unfolded. The only contemporaneous source that attests to the rebellion of 1686 is a letter sent from the Jesuit missionary P. Louis de Mello to R. P. de Noyelle, the leader of the Jesuits (“general de la compagnie de Jésus”), that is also dated 1686 (Bétrand 1850, 376–404). His account of the events is as follows:

To provide for the expenses of war, the king of Mysore exerted on the eastern provinces of its states exactions and cruelties so revolting that his subjects rose en masse against him and against all his ministers. Driven by their weakening losses and current agony and without reflection on the future, as all the enslaved peoples who are deprived of patriotic sentiments, they formed two great armies and chose for their generals two brahmins, leaders of the sects of Viṣṇu and Śiva...

The king of Mysore, outraged at their insolence, dispatched against them an army charged with setting everything to fire and blood, and to pass the rebels at the edge of the sword, regardless of age and sex. These cruel orders were carried out; the pagodas of Viṣṇu and Śiva were destroyed, and their immense revenues were confiscated for the benefit of the royal treasury. Those idolaters who escaped the carnage fled to the mountains and in the forests, where they lead a miserable life.

Bétrand 1850: 377, 380–381, my translation

The letter continues describing how the revolt specifically targeted Christians in the region and the heroes that arose from their ranks to fight for the cause of Christ. While this partisan emphasis in the letter contains obvious exaggeration, the letter blames the king for the insurrection against Mysore in 1686 and identifies religious leaders as its instigators.

The later and more detailed accounts of the colonial-era historians claim to be based on oral histories from the region. These oral histories were recorded in English (Wilks 1869 [1810]) and Kannada (Dēvacandra’s Rājāvaḷi Kathāsāra, Saṇṇayya 1988) and appear alongside the details of Cikkadēvarāja’s pluralistic court from the early nineteenth century described above. Not only do these sources give a more thorough accounting of the rebellion but they relate gruesome tales of treachery, religious persecution, and mass murder.

The first such account of the rebellion was recorded and printed by Mark Wilks, the acting Resident of the British East India Company in the Mysore court of Krishnaraja Woḍeyar III from 1803–1808 (Carlyle 1900: 279–280). Wilks bases his version of the events on a “traditionary account …[that] has been traced through several channels to sources of the most respectable information” (Wilks 1869 [1810]: 129). Like Jesuit missionary P. Louis de Mello, Wilks’s account is replete with allusions of mismanagement that certainly served his role as an agent of the British East India Company, and it seems likely that his version of the story was shaped by Liṅgāyat informers and his personal predilection for their “rational reform” (Wilks 1869 [1810]: 514). The first recorded Kannada version of the events is in the Rājāvaḷi Kathāsāra (1838) that was written by the Jain poet Dēvacandra. Dēvacandra’s account of the story, like the Liṅgāyat version related by Wilks, is told from sectarian perspective, highlighting the ills that were perpetrated on the Mysore Jain community. It also must be noted that Wilks acknowledges in his preface that he worked closely with Mackenzie, who gave Wilks “unlimited access to the study of [his] collection … and to his establishment of learned native assistants” (Wilks 1869 [1810]: xii); therefore, it is extremely likely that Dēvacandra was familiar with Wilks’s account and that they might have even had the opportunity to discuss one another’s version of the events.

Both Wilks and Dēvacandra point to the adoption of royal titles as the very first tension that later erupts into the full-blown rebellion. For Wilks, the problems began when Cikkadēvarāja forced the local, smaller rulers to renounce their royal titles, like woḍeyar, palegāra, and rāja and to join his court in official, albeit diminished, capacities and to cede administration over legal and financial decisions within their realms to the Mysore king. According to Wilks, this angered the “Jungum priests” (i.e., Liṅgāyats) because they had formerly held enormous sway over the courts in these outlying feudatory territories. When the new financial reforms were enforced, the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyats used this as an opportunity to push their followers into revolt.

In Dēvacandra’s account, the controversy focused on the title woḍeyar. During the Vijayanagara Empire, oḍeyar (also spelled voḍeyar, vaḍiyar, etc.) had been an administrative title for a petty chieftain. After the fall of the empire, many of the successor states transformed their titles to family names, such as the title nāyaka. The title woḍeyar would become a point of contention with emerging kings and religious leaders adopting the sovereign title. The Mysore Woḍeyars adopted woḍeyar as their family name while changing their title to rāja and mahārāja. Simultaneously, however, woḍeyar had been adopted as the title for Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat swamis, particularly those who oversaw their religio-political institutions or maṭhas. Dēvacandra suggests that the Vīraśaiva maṭhas had become so powerful that the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat woḍeyars wanted the title to themselves and desired to overthrow the Mysore state (Saṇṇayya 1988: 347).

While both sources agree that the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat leaders stoked the insurrection and cut off Mysore’s revenue stream by encouraging the cultivators to cease agricultural work, Dēvacandra adds that the jaṅgamas and their followers took up arms and forced the king’s representatives out of the region. On the council of his Jain prime minister Viśālākṣa, Cikkadēvarāja sent Firdullā Khān, a junior officer (jamādāra) from his cavalry. After the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat oḍeyars demanded that the Mysore kings cede their authority to the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyats leaders, Firdullā Khān cut down the rebel leaders with a spray of arrows. While this effectively ended the revolt, the demands of the jaṅgamas incensed Cikkadēvarāja, and the king ordered his gurikāra (headman) Nanjē Gauḍa to hunt down the remaining jaṅgamas, destroy their maṭhas, and confiscate their rent-free lands. Gauḍa was efficient in his efforts, rounding up over 1,000 jaṅgamas who were promptly brought before the king and executed. As further punishment, the king ordered the region’s taxes to be raised yet again. For Dēvacandra, however, the events do not end with the victory of the king, but with the assassination of the Jain prime minister Viśālākṣa, whom the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat community held responsible for the slaughter of their leaders and their exorbitant taxes. On his death bed, Viśālākṣa recommends the staunch Śrī Vaiṣṇava minister Tirumalārya, who goes on to effectively consolidate religious authority within his own tradition.

According to Wilks’s rendering of the events, Cikkadēvarāja did not wait for the rebellion to organize. Instead, once the news that labor in the fields had ceased and revenues were no longer being collected arrived, Cikkadēvarāja “adopted a plan of perfidy and horror, yielding in infamy to nothing which we find recorded in the annals of the most sanguinary people” (Wilks 1868 [1810]: 128). The king, then, invited the Vīraśaiva-Līngāyata priests and maṭha leaders to the Śrīkaṇṭhēśvara (a.k.a. Nañjuṇḍēśvarasvāmī) temple in Nañjaṅgūḍu under the pretense of brokering a peace treaty. Four hundred jangamas came for the meeting, and one by one they were led through a labyrinthian walled corridor. At its end they were received by the king to whom they would bow in obeisance. After this formal recognition of the king’s overlordship, the individual leader would be ushered into the next room. Instead of receiving gifts for their participation, which was the custom, they were met by an executioner who beheaded each priest and threw the body into a mass grave. On the very same day, orders were carried out for the destruction of seven hundred Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat maṭhas throughout the kingdom. In the subsequent days and weeks, the king’s men roamed the countryside assassinating anyone wearing an ochre robe and any followers that were with them. After eradicating the leadership, Cikkadēvarāja canceled all of the tax-free land grants given to the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyats and continued with his tax reforms (Wilks 1868 [1810]: 128).

After the revolt was subdued, Wilks’s account continues, Cikkadēvarāja eliminated the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyats from the Woḍeyar court and installed a new Śrī Vaiṣṇava prime minister, Tirumalārya. Though Vīraśaiva-Līngāyatas were not formally forbidden from his court, a royal decree issued by Cikkadēvarāja in 1693 forbade non–Śrī Vaiṣṇava sectarian marks in the Mysore court, effectively ostracizing anyone who wore the Liṅgāyat liṅga (Rao 1948: 365). Instead, the primary criterion for full participation in the court was affiliation with the Śrī Vaiṣṇava tradition, which was signified by initiation through the five rites (pañca-saṁskāra) and the correct continued performance of Śrī Vaiṣṇava rituals (Rao 1948: 365).

For both Wilks and Dēvacandra, Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyats were systematically excluded from participation in the court, not as a result of their beliefs or practices, but as a consequence of their role in the rebellion. According to these sources, after 1686, Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat ritual and practice had no place in the Woḍeyar religious worldview; they were effectively outsiders. Whenever we consider the context during which these new details for the rebellions emerged, there is an additional layer of complexity to understanding the role Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat identity in the politics of southern Karnataka. Published in 1810 (Wilks) and 1838 (Dēvacandra), both accounts of the Revolt of 1686 appeared during the reign of Kr̥ṣṇarāja Woḍeyar III, and on either side of the rebellion of 1830–1831, as a result of which he would eventually lose his power. As with the colonial-era details of the Revolt of 1686, historians claim that the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat community were catalysts for the insurgency. Through this context, we can better understand the role of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat identity as a political concern in Mysore in the early nineteenth century and how this might have shaped the colonial-era histories of the seventeenth-century revolt.

The Rebellion of 1830–1831

We now turn to the rebellion that was just mentioned, namely, the Nagara Rebellion of 1830–1831 ce, or the “Peasant Insurgency,” as Burton Stein has called it. This rebellion took place in the Mysore kingdom during the reign of Kr̥ṣṇarāja Woḍeyar III (r. 1799–1868 ce) and was one of the reasons adduced by the British East India Company to strip the king of his administrative sovereignty. Similar to the rebellion during Cikkadēvarāja’s reign, the Nagara Rebellion arose in reaction to land-tax reforms, and the Mysore court held the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat community responsible. Though the rebellion was quickly subdued, the the rebellion of 1830–1831 led to the weakening of Mysore kingship and the strengthening of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyatism into the center of Mysore royal practice.

Like the Revolt of 1686, the Nagara Rebellion started in the northeastern portion of the kingdom in the Śimōga district (tālūk) of the Nagara governorship (fauzdāri). The chieftains of this area claimed descent from the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat Keḷadi Ikkēri kings and contested Kr̥ṣṇarāja III’s rule during the early years of his reign (he was installed by the British at four years old after the defeat of Ṭipū Sultān in 1799). However, the Britishf orces quickly quelled this descent in order to solidify Kr̥ṣṇarāja III’s shaky claims to the throne.1 The hesitation of the Nagara chieftains to support the newly “restored” king earned them steeper taxes under the cash tax system instituted during the famous administrator Pūrṇayya’s time as Kr̥ṣṇarāja’s divan (Stein 1985: 15–16). The tension subsided for a while, but the chieftains of this peripheral zone soon challenged the authority of the Woḍeyar king once again. Buḍi Basappa, a wealthy chieftain of Nagara, proclaimed himself to be the king (rājā) of Nagara, descendant of the Keḷadi-Ikkēri kings. The new “king” immediately called upon agriculturalists of the region to stop paying taxes to Mysore and join his cause to revoke the king’s claim to sovereignty in the territory. The rebellion spread to other regions of the Mysore kingdom as agriculturalists from the fauzdāris of Madhugiri, Aṣṭagrāma, and Bangalore ceased paying taxes and joined in violent revolt.

-

1For more regarding the precarity of Kṛṣṇarāja’s claim to the throne vis-à-vis Ṭipū Sultān’s sons, see Simmons 2020: 113, 129 n. 34.

While most subsequent scholarship (Gopal 1960; Stein 1985; Gopal and Prasad 2010), has followed the British colonial-era account in presenting the rebellion as essentially a tax revolt, the role of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyatism in the spread of the 1830–1831 rebellion should not be understated, especially in its claims of sovereign authority by the new king of Nagara, Buḍi Basavappa. Before he was Buḍi Basavappa, the new king was a petty criminal named Śāradāmalla (lit., “Saraswati’s hero”). Śāradāmalla met a Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat jaṅgama who claimed to be the former purōhita of the final Keḷadi Nāyaka Channabas(av)appa (r. 1754–1757), who ruled prior to Nagara’s fall to Ṭipū Sultān’s father Haidar Ali and the Keḷadi kingdom’s incorporation as territory of Mysore. The former Keḷadi purōhita had in his possession the insignia of the erstwhile royal family and vested the authority of the Keḷadi kingdom on Śārādamalla by bestowing him with the royal insignia and claiming that he was actually the son of the final ruler of the Keḷadi kingdom in Nagara. Endowed with the outward signs of royalty and the genealogy of the Keḷadi rulers, Śāradāmalla adopted the name Buḍi Basavappa (lit. “Basavappa’s Descendant”) and began raising an army.

The Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat elites served as the mouthpieces of the rebellion, who read the dissenters’ propaganda to the “peasants” (Stein 1985: 15). The Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat population—30% of the region—was quickly mobilized by the networks of jaṅgamas and their call to action. Hesitant members of the community were further prodded to join the revolt through threats of excommunication from the sect via pronouncement of pollution or, even worse, having “horns and bones of animals thrown into their houses” if they did not fall in line with the insurgency (Stein 1985: 18).

By the beginning of 1831, the Mysore administrators and their forces had been effectively ousted from Nagara, causing the British East India Company troops to step in and take the region back for the Mysore kingdom. In the wake of the rebellion and a lengthy study of its causes, British administrators decided that rebellion was a result of Kr̥ṣṇarāja III’s mismanagement of finances and his appointment of administrators ill-suited to perform their duties for the benefit of the state (Hawker et al. 1833). Therefore, Kr̥ṣṇarāja III’s direct rule of the Mysore kingdom ended, and the administration of the kingdom was bequeathed to a series of British Commissioners. In the deliberations that led to this decision, British correspondence makes the case that Kr̥ṣṇarāja III had no dynastic sovereign claims over the region of Nagara, which had formerly been part of the kingdom of Keḷadi. It had been incorporated into the kingdom of Mysore through the rights of conquest during the period of the usurpers Haidar Ali and Ṭipū Sultān, who had conquered the region in 1763 and 1782, respectively, and established themselves as the kings of Nagara.2 Nagara had only become the possession of the Wodeyar kings through the Subsidiary Treaty of 1799 after the death of Ṭipū Sultān.

-

2The city at the time was called “Bidanūru” but was renamed Haidarnagara (“City of Haidar”) by Ṭipū Sultān. After the fall of Ṭipū Sultān, the name was shortened to Nagara.

As I have argued elsewhere (Simmons 2020), in the subsequent years of his reign, Kr̥ṣṇarāja III and his court emphasized his “Hindu” identity—even using the term—as he attempted to situate himself into the British historiography of India. This was done in an attempt to justify his claims to kingship, not on the grounds of the “rights of conquest” but through religious identity as the rightful “ancient Hindu rajah” of Mysore (Simmons 2020: 107–132). Kr̥ṣṇarāja III argued for his sovereignty over the region through both explicit and implicit claims of Hindu identity and kingship, framing himself as a king for all Hindus. In addition to theoretical framing of his sovereign authority, a consolidated Hindu identity served as a means to unite the various religious traditions of southern Karnataka under one larger unified political banner. Therefore, Kr̥ṣṇarāja III thoroughly incorporated Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyatism into his ritual and devotional life in an attempt to consolidate support through appeals to a Hindu identity (see Stoker 2016). Kr̥ṣṇarāja III went to such great lengths to demonstrate his acceptance of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyatism that he was initiated into the tradition and incorporated it into the Woḍeyars’ origin narrative.

The most thorough account that connects Kr̥ṣṇarāja III to the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat tradition is detailed in the Śrīmanmahārājavara Vaṁśāvaḷi (or Lineage of the Kings of Mysore, ca. 1867), a lengthy history of the Mysore kings that is attributed to the king himself. The text traces the lineage of the Woḍeyars from the creation of the cosmos to Kr̥ṣṇarāja III, particularly focusing on the period following the migration of the Wodeyar progenitor Yadurāya to Mysore in 1399 ce. It is in this narrative of the establishment of the Wodeyar kingdom in Mysore that Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyatism is embedded into Wodeyar sovereignty through the authority of a jaṅgama. The text tells us that Yadurāya and his brother Kr̥ṣṇarāya traveled to Mysore and immediately made a pilgrimage to Chamundi Hill to see the goddess Cāmuṇḍēśvari, who was supposed to give them a kingdom over which they would rule. After worshiping the goddess, she appeared before the brothers and told them to go to the goddess Uttanahalli’s temple and then “to go the Kōḍibhairava temple beside the pond, which is behind the temple of Īśvara who was worshiped by the R̥ṣi Tr̥nabindu that is on the East side of Mysore city, and stay there. At that time, a man wearing a liṅga and the robes of a jaṅgama will come. When he sees you, he will say a few words” (Wodeyar 1916: 4–7, my translation; see also Simmons 2020). The brothers did as they were told and the next morning they met a jaṅgama. After a brief conversation about the brothers’ background and their journey to Mysore, the jaṅgama told them of the evils that had beset Mysore and its former rulers and that another jaṅgama would come give them instructions on how to take the city. At this point, the mendicant vanished, and the brothers realized that the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat mendicant had been none other than Śiva in his manifestation as Śrīkaṇṭhēśvara, the deity who lives at nearby Nañjaṅgūḍu. They vowed right then and there that, just as Cāmuṇḍi is their family goddess, Śrīkaṇṭhēśvara will be their family god, in marked contrast to the slaughter of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyats in the Śrīkaṇṭhēśvara of Nañjaṅgūḍu during the revolt of 1686 as described in Wilks’s history. The centrality of the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat tradition in the foundation of the Mysore Wodeyar kingdom is further reiterated later in the narrative at Yadurāya’s coronoation in the Śrīmanmahārājavara Vaṁśāvaḷi: “Having made [Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyatism] their family tradition as requested by the jaṅgama, who had been pleased by their actions, the brothers commanded that all subsequent rulers would be called by the name Woḍeyar, and that saffron cloth, the symbol and vestment of the jaṅgamas, be included in their flag (Wodeyar 1916: 7, my translation).

This small reference is easy to overlook but is crucial for the refashioning of the Woḍeyar kings as sovereigns authorized by Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyatism as a result of their piety and devotion. As mentioned earlier, the term oḍeyar was a medieval term employed within imperial administration that denoted a small local vassal. This title was given to Bōḷu Cāmarāja IV by the Vijayanagara viceroy in 1573. The Woḍeyar clan certainly developed their family name from this petty administrative and political position within Vijayanagara polity as a way to maintain royal authority as the empire crumbled. The term oḍeyar had also developed into a title for a leader within the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat network of priests. By providing an alternate origin of the Woḍeyar family name, instead of tracing their name from the Vijayanagara imperium, the Śrīmanmahārājavara Vaṁśāvaḷi connects the entire lineage to Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat leaders, resolving the tension over the title that Dēvacandra claimed had been the source of the 1686 rebellion.

The origin story of the Śrīmanmahārājavara Vaṁśāvaḷi, which was written approximately thirty-five years after the rebellion of 1830–1831 and the subsequent British takeover, is the first extant record of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat influence in the Wodeyar origin story. It, therefore, can only be understood in the context of the previous revolt as a post hoc attempt to make a place of prominence for the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat community within the devotional worldview of Kr̥ṣṇarāja III’s kingdom. Just as in the case of Buḍi Basavappa, this devotional alliance with Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat priests and their religious institutions worked to retroactively bestow spiritual and sovereign power to the Wodeyar king whose authority was questioned and sovereignty challenged.

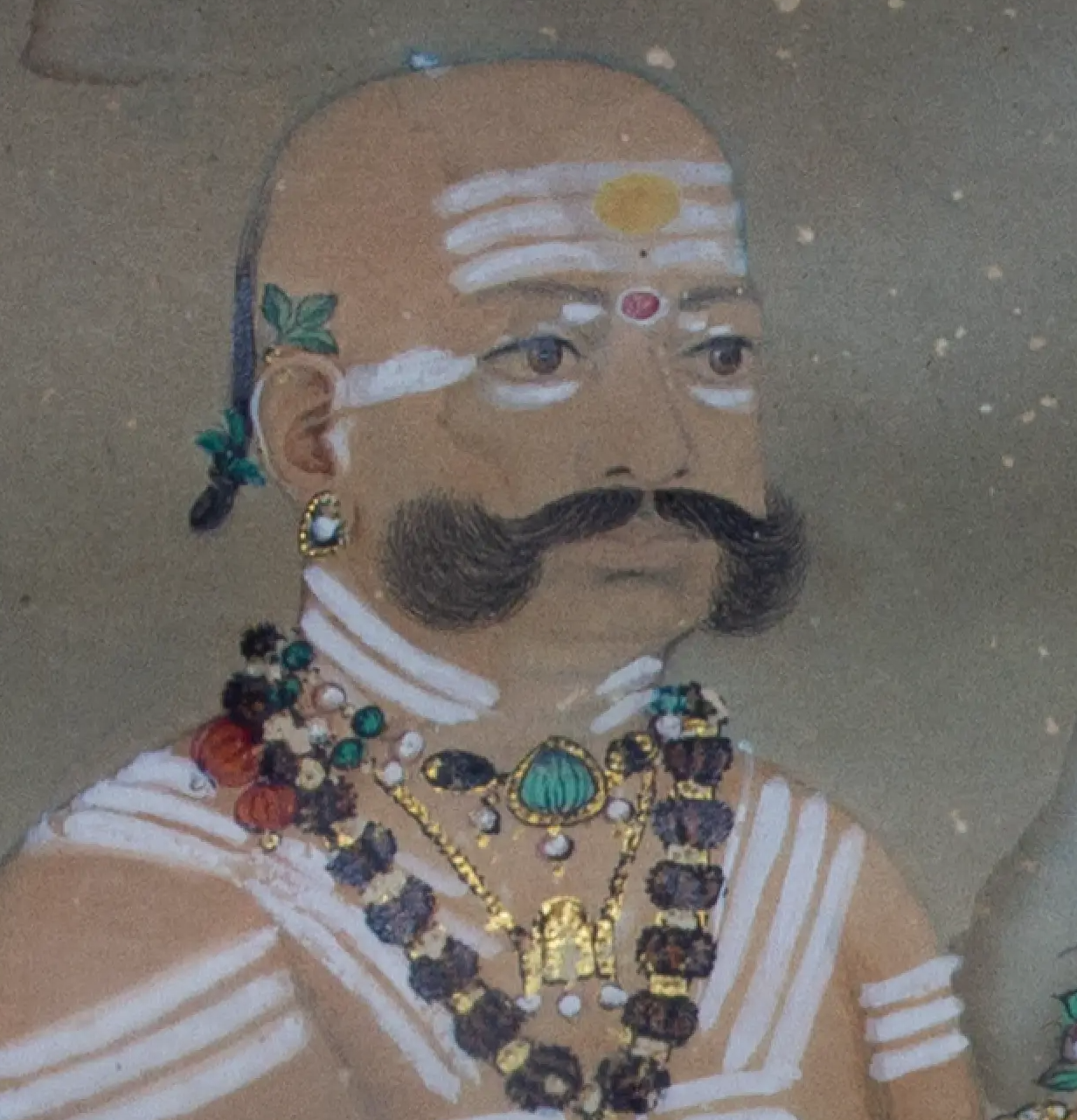

Figure 2

Detail of iṣṭaliṅga from figure 1.

The bonds between Kr̥ṣṇarāja III and Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat community were further strengthened through the production and circulation of portraits of the king, a common practice of the Mysore kings to display devotional preferences and alliances in early modern and colonial period (Simmons 2020). Kr̥ṣṇarāja III’s devotional imagery was far more extensive than his predecessors, including paintings and prints, ranging from large murals to frontispieces of mass-produced books, of the king conducting rituals that were circulated throughout his kingdom and abroad. While most of the devotional images of Kr̥ṣṇarāja III focused on the goddess Cāmuṇḍēśvari or Śrī Vaiṣṇava practice, several extant portraits portray the king wearing the outward signs of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat devotion, a personal iṣṭaliṅga (figure 1), and conducting Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat ritual to his personal liṅga (figure 3). Through this display of his pious practice Kr̥ṣṇarāja III incorporated the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat practice within the royal ritual repertoire, projecting his new persona as the Hindu king and the king for all Hindus for both his subjects and his British overlords, regardless of whether or not Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyats considered themselves to be part of his Hindu fold (see Simmons 2020).

Conclusion

Through these two case studies, I have attempted to shed light on the construction of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat identity vis-à-vis political authority and structures within early modern and colonial Mysore to provide us with an opportunity to think about external factors that shape religious identities. The inclusion or exclusion of a religious tradition—in our case the exclusion of the Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat tradition from the allegedly pluralistic court of Cikkadēvarāja and its inclusion within the “Hindu” court of Kr̥ṣṇarāja III—and, therefore, the determination of one’s religious identity has a history of being a contentious topic in the political arena. Exclusion and inclusion, othering and appropriation, are not simply unidirectional or macro-level processes; instead, they are dynamic and fluid positions that change in response to a variety of stimuli. Additionally, the construction of religious identity is often beyond the purview of the tradition itself, but it is shaped, and often mandated, from the outside.

Returning to the framing mechanism of contemporary Liṅgāyatism, this history allows us to see continuity and fracture with the past. As alluded to above, Liṅgāyats began their movement to be considered a separate religion in the 1920s. This movement too was not without external factors. If Liṅgāyatism were recognized as a religion distinct from Hinduism, its practitioners would be afforded the rights of minority religions. This movement, however, has never been entirely representative of the Liṅgāyat community as a whole, which like most religious traditions is not monolithic or heterogeneous. Over the decades since Independence, the majority Liṅgāyat political alliance has shifted between different political parties, often gravitating toward Hindu nationalist positions. Indeed, in the aftermath of Siddaramaiah’s decision, prominent leaders and heads of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat maṭhas came together to pass a resolution against the government’s decision. Even the decision about Liṅgāyat identity led to accusations from prominent Liṅgāyats that the Congress Party was attempting to divide the Hindu community (Shivasundar 2023). Congress eventually lost the election, including in Liṅgāyat-dominated regions, and Siddaramaiah lost as chief minister of Karnataka. This conclusion is not intended to tread into the territory of analyzing contemporary politics. Certainly, as the postscript to Siddaramaiah’s 2018 decision about Liṅgāyatism demonstrates, the identity of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyat’s and its inclusion and exclusion is still an ongoing discussion. The history of Vīraśaiva-Liṅgāyatism’s role in the court of Mysore, however, can help us to understand the complex historical and cultural context that shape contemporary politics and debates and help us to better understand the role political expediency play in the shaping of religions and religious identity.

Notes

-

↑For more regarding the precarity of Kṛṣṇarāja’s claim to the throne vis-à-vis Ṭipū Sultān’s sons, see Simmons 2020: 113, 129 n. 34.

-

↑The city at the time was called “Bidanūru” but was renamed Haidarnagara (“City of Haidar”) by Ṭipū Sultān. After the fall of Ṭipū Sultān, the name was shortened to Nagara.

References

- Bétrand, P.J. 1850. La Mission du Maduré: d’Après des Documents Inédits. Volume III. Paris: Librairie de Poussielgue-Rusand.

- Boyarin, Daniel. 2004. Border Lines: The Partition of Judaeo-Christianity. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Carlyle, Edward Irving. 1900. “Mark Wilks” in Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 61. Edited by Sidney Lee. London: Smith, Elder, and Co.

- Chidester, David. 1996. Savage Systems: Colonialism and Comparative Religion in Southern Africa. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Cikkadēvarāja. 1905. Cikkadēvarāja Binnapam. Mysore: Karnataka Kavya Kalanidhi, 1905.

- Saṇṇayya, B. S. (ed.). 1988 [1838]. Dēvacandra Viracita Rājāvaḷi Kathāsāra. Mysore: University of Mysore Press.

- EC [Epigraphia Carnatica] Volumes 1-12. 1898–1905. Bangalore: Government Press.

- Gopal, M. H. 1960. The Finances of the Mysore State, 1799-1831. Bombay: Oriental Longmans.

- Gopal, R. and S. Narendra Prasad. 2010. Krishnaraja Wodeyar III: A Historical Study. Mysore: Directorate of Archaeology and Museums.

- Hawker, Thomas; Morison, William; Macleod, J M; Cubbon, Mark. 1833. Report on the Insurrection in Mysore. Bangalore: Mysore Government Press.

- Home Miscellaneous Series. Vol. 709. British Library Office India Office Records.

- Orsi, Robert A. 2006. Between Heaven and Earth: The Religious Worlds People Make and the Scholars who Study Them. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Rice, B. Lewis. 1897 Mysore: A Gazetteer Compiled for Government. Volume II. Westminster: A. Constable.

- Rao, C. Hayavadana. 1948 History of Mysore 1399–1799. Vol. 1. Mysore: Superintendent of the Government Press.

- REC [Revised Epigraphia Carnatica] Volumes 1-16. 1972–2009. Mysore: Institute of Kannada Studies University of Mysore.

- Sastri, S. Srikanta. 1941. “Jaina Traditions in Rajavali Katha.” The Jaina Antiquary 7.1 & 11 (December). https://www.srikanta-sastri.org/jain-traditions-rajavali-katha/4589254219.

- Śāstri, V. Prabhākara. 1920. Cātupadyamaṇimañjari. Madras: np.

- Shivasundar. 2023. “How Karnataka’s Lingayat Community Was First Hinduised and Then Hindutvaised” May 8. https://thewire.in/politics/karnataka-election-lingayat-hindutva (accessed August 15, 2023).

- Simmons, Caleb. 2020. Devotional Sovereignty: Kingship and Religion in India. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Stein, Burton. 1985. “Notes on 'Peasant Insurgency' in Colonial Mysore: Event and Process.” South Asia Research 5 (1): 11–26. DOI 10.1177/026272808500500102.

- Stoker, Valerie. 2016. Polemics and Patronage in the City of Victory: Vyasatīrtha, Hindu Sectarianism, and the Sixteenth-Century Vijayanagara Court. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Times of India. 2018. “Karnataka govt clears minority status for Lingayats.” March 20. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/karnataka-govt-clears-minority-status-for-lingayats/articleshow/63373048.cms. (accessed Jan 19, 2021).

- Wadayar, Maharaja Chikadevaraja. 1949 Chik-Devaraja Binnapam: Being a Discourse on the Essence of Visishtavvaita. Edited by R. Tirunarana Iyengar. Mysore: Coronation Press.

- Wilks, Mark. 1869 [1810]. Historical Sketches of the South of India in an attempt to trace the History of Mysoor from the Origin of the Hindoo Government of that State, to the Extinction of the Mohammedan Dynasty in 1799. Madras: Higginbotham and Co.

Revision history

- 2024-08-19 (Andrew Ollett): Conversion to TEI from DOCX document.

- 2024-11-10 (Andrew Ollett): Changes to first proofs.

- 2024-11-16 (Andrew Ollett): Changes to last proofs.