Introduction

Early in May 1911, the residents of Kolhapur braced for a riot. The city’s Vīraśaivas planned to celebrate the arrival of a prominent monastic leader with a procession. Anticipating backlash, organizers asked Kolhapur’s nominal ruler, Chhatrapati Rajarshi Shahu (descendent of the Maratha leader Shivaji Bhonsle), to personally approve the event. Shahu later recalled in his memoirs that Brahmans in the city “threatened a breach of the peace” were the procession to take place.1 They objected not to the arrival of a prominent religious figure, or even to using city streets as a stage for Vīraśaiva piety. Kolhapur’s Brahmans objected to a specific processional object—the severed arm of Vyāsa, fabled author of the Mahābhārata. Made of bundled rags or gnarled wood, an effigy of Vyāsa’s severed arm—known in Kannada simply as Vyāsantōḷ (Vyāsa’s arm)—would dangle atop a tall pole alongside cymbals, streamers, and a flag decorated with the image of Śiva’s bull, Nandin. During the procession, devotees would hoist the pole aloft while dancing and singing. Some might even swing at Vyāsa’s arm with sticks or swords, reenacting an event from Purāṇic lore when Nandin lopped off Vyāsa’s arm in a fit of pious rage.

Vyāsa’s severed arm had sparked violence elsewhere in the Deccan. There were riots in Bellubbi in 1882, and the Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency reported in 1884 that “many lives were lost” during a conflict in Dharwad a few decades earlier.2 “Formerly riots were of constant occurrence,” the Gazetteer reads. “The parading of Vyāsa’s hand was forbidden, but in outlying villages the practice is still kept up.”3 Vyāsa’s arm may have put parade-goers and passersby at risk, but it seems to have been especially dangerous for organizers. In 1830, at the request of Brahmans in the western reaches of the Mysore state, Krishnaraja Wodeyar III ordered the execution of two Vīraśaiva leaders for organizing a Vyāsa procession.4 Despite the potential for bloodshed, Shahu approved the parade in Kolhapur and promised his royal marching band as a token of support.

-

4Wodeyar’s dispensation was found in the library of the Sringeri Śāṅkara maṭha at Koodli (near Channagiri) in 1945. Collectors deduced that Wodeyar sent a copy of the decree to Brahmans at the maṭha because they petitioned the court to intervene in the procession. Doing so may have endeared Wodeyar to the region’s Mādhva and Smārta Brahmans at a moment when their support was vital to securing Mysore’s power over western Karnataka. It is unclear whether a copy of the document was also sent to the Akṣobhyatīrtha Mādhva maṭha in Koodli. See sannad no. 3 in the “Sannads of the Mysore King Mummadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar,” in Annual Report (1946).

The controversy about Vyāsa’s body in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was, of course, a product of a particular place and time. The establishment of British common law in the subcontinent, for instance, required that both defenders and challengers of Vyāsantōḷ adopt new conceptual and legal categories. But Vyāsantōḷ was not an iatrogenic product of colonial law, which is to say that it was not produced by the advent of colonial law itself.5 Though British courts had a hand in refiguring Vyāsantōḷ along new conceptual lines, the rhetoric and perhaps even the practice of Vyāsa desecration is evident as early as the late sixteenth century.

This article examines the first known anti-Vyāsantōḷ writing, a short Sanskrit poem titled Praising Vyāsa, Condemning the Apostates (Pāṣaṇḍakhaṇḍanavyāsastōtra).6 Written by Vādirāja Tīrtha (ca. 1550–1610), an influential poet, scholar, and proselyte of Madhva’s dualist Vedānta, Praising Vyāsa provides a starting point for not only plotting the murky history of a particular controversy, but also for rethinking prehistories of religious conflict to include textual polemics and philological disputes.

By invoking the language of religious conflict, I am, of course, thinking of Christopher Bayly and his work on riots in late precolonial and early colonial north India.7 Bayly was working against at least two accounts of conflict in the subcontinent. The first was only “dimly aware” of religious violence prior to the rise of colonial commercial power, and the second, while acknowledging the fact of precolonial religious violence, nevertheless maintained that its “quality and incidence” changed dramatically after 1860. Bayly advanced a position of continuity, in which moments of religious conflict in the late nineteenth century are thought to have analogues in the early colonial period. These earlier moments were linked not to religious revivalism or civilizational clashes, Bayly suggested, but to localized shifts of resources and power. Bayly’s work has invited nuancing and criticism since it was written in 1985, but few have challenged the way Bayly consigned texts and their interpretation to little more than symbolic outgrowths or second-order effects of politics and economy.8

This article examines the textual prehistories of what became, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a site of violent agitation and acrimonious litigation. Through a close reading of Praising Vyāsa and related texts, I argue several things. First, no Vyāsantōḷ text was itself the pretext for conflict. Nor were Vyāsantōḷ texts the mere sublimation of strife on the ground. The desecration of Vyāsa’s body and its ceremonial display in city streets in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries emerged from an interplay of text and practice—a kind of mimetic loop—in which forms of interpretation informed paradigms of performance and vice versa.

The movement between reading, performance, and public spectacle was accelerated in part by Vyāsa’s migration from a fictive figure of epic antiquity to a centerpiece of devotion among Vaiṣṇavas of various orders, and especially among a community of Viṣṇu devotion and Vedānta organized around the figure of Madhva (ca. 1238–1317 CE ). Styled as both an emanation of Viṣṇu as well as Madhva’s guru, Vyāsa imparted to Madhva’s writings, and by extension to his dualist Vedānta philosophy, both soteriological and scholastic legitimacy. It is unsurprising, then, that followers of Madhva wrote numerous Vyāsa praise poems and that even the notional desecration of Vyāsa’s body would be interpreted as an affront to the very affective and soteriological core of Madhva’s devotional community.

Whether Vyāsa’s arm was a processional object before the early nineteenth century is unclear. Even its presence in writing before the nineteenth century is fleeting. The second part of this article puts forward a provisional genealogy of Vyāsantōḷ. Episodes of divine dismemberment are not uncommon in Sanskrit literature, and the case of Vyāsa’s arm appears to adapt and amplify earlier motifs of “aggressive bodily intervention” seen in Sanskrit epics, Śaiva Purāṇas, and Vīraśaiva didactic texts.9 The closest parallel to the amputation of Vyāsa’s arm is its paralysis. I look at several examples of Vyāsa’s monoplegia. The first is from the Skanda Purāṇa, where Vyāsa confronts Śiva with a sermon about Viṣṇu’s superiority and is paralyzed in turn. Similar moments of paralysis are found in earlier texts, including the Mahābhārata and the Śivadharmōttara. Yet these cases of paralysis are usually reversed and are thus symbolically distinct from the permanent dismemberment of Vyāsantōḷ. Earlier motifs of paralysis appear to have undergone a consequential intensification in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This is apparent, for instance, in Vīraśaiva didactic texts like Śivayogin’s (ca. fourteenth century CE ) Siddhāntaśikhāmaṇi and its early-modern commentaries, where Śiva’s slanderers are met with more egregious forms of bodily harm.

-

9See Jesse Pruitt’s forthcoming work on the Śivadharmōttara.

Here I must emphasize that these were textual dictates, and that the gap between text and life on the ground—at least where they concern violence against those who challenge Vīraśaivas and their institutions—appears to have been vast indeed. When Vādirāja wrote Praising Vyāsa in the late sixteenth century, swaths of his home in western Karnataka were controlled by a powerful Vīraśaiva ruling family. Rather than curse or kill critics of Vīraśaivas, the Nāyakas of western Karnataka lavished them, including Vādirāja, with royal largesse.

The sources I present here show Vyāsa’s arm as a surrogate for several things simultaneously. By the end of the sixteenth century, it had become a token of sectarian triumph, where Śiva could win over the most ardent devotee of Viṣṇu, even if only by force. For Vādirāja, the desecration of Vyāsa was both an egregious textual misinterpretation and an unforgivable attack on the legitimacy of Madhva and his Vedānta. What I do not touch on here, but which hangs over the entire Vyāsantōḷ controversy, is caste. Vyāsa’s venerated position among Vaiṣṇava and Śaiva Brahmans alike would have rendered his desecration a potent symbol of anti-caste agitation. And with the rise of the Vīraśaiva ruling family of western Karnataka, the flagrant desecration of an exemplar of caste elitism may have marked a turn in subaltern political power and its symbolic expression.

I conclude with a perfunctory examination of Vyāsantōḷ’s juridical life, which allows me to highlight at least two avenues of further research. The first might be a new direction in the study of the Mahābhārata. While anthropologists and historians have noted the Mahābhārata’s various localizations and retellings, Sanskrit epics as points of sectarian, caste, and legal conflict are largely unstudied. Second are the legal afterlives of premodern Sanskrit polemics in colonial India. I have in mind both the direct and indirect ways that precolonial Sanskrit disputes, especially over issues of inheritance, property, marriage, temple access, procession, and so on, shaped legal discussions in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. But early modern Sanskrit polemics about Vyāsantōḷ are interesting not because of their influence on later legal debates, but because they appear to have had no influence at all. Though Vyāsa’s body remained a source of outrage, modes of what we might call “philological containment”—erudite (if still vitriolic) Sanskrit polemics as a strategy of conflict management—seem to have given way to political violence and courtly machinations.

Conjuring the Image of Vyāsa

Vyāsa was probably never a real person, though some of the deeds ascribed to him may have been the work of many people over many centuries.10 Yet when Vādirāja wrote Praising Vyāsa, Condemning the Apostates in the late-sixteenth century, Vyāsa had long been transformed into a god. To do justice to his divinization alone would warrant a separate study.11 My starting point here, however, is Vyāsa after apotheosis.

-

10Later Purāṇas speak of as many as eighteen Vyāsas. See Viṣṇupurāṇa 3.3.9 (ed. Sampatkumārācārya 1972: 191).

-

11The figure of Vyāsa has accumulated a considerable scholarship. A study of his divinization alone would include Shembavnekar (1947), who showed that “Vyāsa had nothing to do with the four Vedas.” It would include volumes written about Vyāsa in the field of Mahābhārata studies, such as Sullivan (1999) and also studies on specific chapters and sections of the Mahābhārata. Grünendahl (1989 and 2002, and Grünendahl and Schreiner 1997) for instance, describes how Vyāsa became an “emanation of Nārāyaṇa,” and the scholarship of Biardeau (2002), Hiltebeitel (2005), and others has convincingly shown the Nārāyaṇīyaparvan to be a later feature of the epic and to reflect the interests of new cults of Viṣṇu worship in the first centuries CE . Such a study would also include work on Vyāsa in the Purāṇas, like Saindon (2004–2005) and Bisschop (2021).

Vyāsa’s identity as Viṣṇu had not only been a given for Madhva and his early followers; it was vital for establishing Madhva’s legitimacy as a Vedānta commentator. Vyāsa plays an especially prominent role in Madhva’s Determining the Ultimate Aim of the Mahābhārata (Mahābhāratatātparyanirṇaya), which emplots the tenets of Madhva’s Vedānta within the narrative arcs of the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyaṇa. In addition to peppering the commentary with his own Vyāsa encomia, Madhva dutifully reiterates the few existing Mahābhārata verses that equate Vyāsa with God. “You should know Kr̥ṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vyāsa as the Lord Nārāyaṇa,” Madhva repeats.12

-

12See Madhva’s Mahābhāratatātparyanirṇaya (ed. Gōvindācārya), v. 2.41, and Mahābhārata 12.334.9 (ed. Sukthankar and Belvalkar):

kr̥ṣṇadvaipāyanaṁ vyāsaṁ viddhi nārāyaṇaṁ prabhum

One of the “ultimate aims” Madhva wanted his readers to take from his Mahābhārata commentary was that Viṣṇu-as-Vyāsa sanctioned both Madhva’s divine nature and his dualist Vedānta project. In the commentary’s second chapter, for instance, Vyāsa announces Madhva as an incarnation of the god Vāyu. Citing a verse from the Bhaviṣyatparvan, but which is not found in any recension of the text, Vyāsa proclaims:

tasyāṅgaṁ prathamaṁ vāyuḥ prādurbhāvatrayānvitaḥprathamō hanumān nāma dvitīyō bhīma ēva capūrṇaprajñas tr̥tīyas tu bhagavatkāryasādhakaḥtrētādyēṣu yugēṣv ēṣa saṁbhūtaḥ kēśavājñayā

The first subsidiary of Viṣṇu is Vāyu,

who has three worldly manifestations.

The first is called Hanumān, the second, Bhīma.

But the third is Madhva, fulfiller of God’s deeds.

At Viṣṇu’s decree, Vāyu has appeared in the first three epochs.13Madhva, Mahābhāratatātparyanirṇaya (ed. Gōvindācārya, vv. 2.124–125, pp. 88–89)

The clamor that Madhva’s messianic self-styling caused in the centuries after his death obscured the messenger himself. Strictly speaking, Madhva did not announce his own divine nature, Vyāsa did. As an emanation of Viṣṇu, Vyāsa transformed Madhva’s unprecedented claim of his own divinity into a scriptural dictate. To deny Vyāsa’s declaration of Madhva’s divine nature, in other words, would be tantamount to denying the authority of the Mahābhārata itself.

Elsewhere, Madhva invokes Vyāsa as his guru, which allowed for elaborate narratives about Madhva’s connection to Vyāsa in early hagiographies. Nārāyaṇa Paṇḍita (ca. fourteenth century CE ), for instance, devotes the seventh chapter of his Śrīmadhvavijaya to narrating Madhva’s visit to Vyāsa’s Himalayan hermitage. Daniel Sheridan has shown how this episode connects Madhva and his writings to Vyāsa by asserting a direct student-teacher relation.14 But this didactic connection is, by measure of verse, an utterly minor feature of Madhva’s life story. Far more significant, both as a narrative fact and for their influence on devotional practice, are the dozens of verses Nārāyaṇa devotes to Madhva’s inner monologue upon seeing Vyāsa in the flesh.15 “Even though Madhva had always seen Vyāsa in his pure, lotus heart,” Nārāyaṇa writes, “upon seeing Vyāsa again anew, Madhva became wonderstruck and thought the following to himself.”16 The next thirty verses describe Madhva’s cascade of observations about Vyāsa’s body, from the dust on Vyāsa’s feet to the matted hair on his head. Madhva’s life story, in other words, takes a sharp detour into Vyāsa encomia. About Vyāsa’s feet, for instance, Madhva thinks to himself:

-

15Concealed from ordinary people during the Kali Age, Vyāsa nevertheless welcomes Madhva’s mind and eyes (cetōnayanābhinandana). Nārāyaṇa likens Vyāsa’s disappearance from the vision of ordinary people in the Kali Age to the disappearance of the sun at night (Nārāyaṇa Paṇḍita, Śrīmadhvavijaya [ed. Gōvindācārya] v. 7.22).:

adhunā kalikālavr̥ttayē savitēva kṣaṇadānuvr̥ttayējanadr̥gviṣayatvam atyajad bhagavān āśramam āvasann imam -

16Nārāyaṇa Paṇḍita, Śrīmadhvavijaya (ed. Gōvindācārya v. 7.17):

nijahr̥tkamalē ’tinirmalē satataṁ sādhu niśāmayann apiavalōkya punaḥ punar navaṁ tam asau vismita ity acintayat

kamalākamalāsanānilair vihagāhīndraśivēndrapūrvakaiḥpadapadmarajō ’sya dhāritaṁ śirasā hanta vahāmy ahaṁ muhuḥpraṇamāmi padadvayaṁ vibhōr dhvajavajrāṅkuśapadmacihnavatnijamānasarāgapīḍanād aruṇībhūtam ivāruṇaṁ svayamnanu kēvalam ēva vaiṣṇavaṁ śritavantaḥ padam ātmarōciṣātamasō ’py ubhayasya nāśakā vijayantē nakharā navaṁ ravimsukumāratarāṅgulīmatōḥ padayōr asya nigūḍhagulphayōḥupamānam ahō na dr̥śyatē kavivaryair itarētaraṁ vinā

Wow! I have the dust of Vyāsa’s lotus feet on my head, the same dust that Lakṣmī, Brahmā, Vāyu, Garuḍa, Śeṣa, Śiva, and Indra once had on theirs. I bow to the lord’s two feet, which are marked with Viṣṇu’s banner, lightning bolt, goad, and lotus. Though naturally ruddy, his two feet appear to have become even more so after beating back the mental passions of his followers. His toenails, which have taken refuge at Viṣṇu’s feet, destroy two kinds of darkness (internal and external) with their luster, and thus surpass even the sun at daybreak. Except for one or the other foot, the best poets fail to find an adequate analogy for Vyāsa’s two feet, which have the most delicate toes and concealed ankles.17

Nārāyaṇa Paṇḍita, Śrīmadhvavijaya (ed. Gōvindācārya v. 7.25–28)

-

17The verb śritavantaḥ in verse 27 conveys that the toenails are both connected to and have taken refuge at Viṣṇu’s feet, much as a disciple might. The suggestion seems to be that just as the toenails remove darkness and surpass the sunrise in their splendor, so too the disciple—in this case, Madhva—can do the same.

Madhva’s encounter with Vyāsa allowed Nārāyaṇa to conjure an intimate portrait of Vyāsa’s body in the minds of his readers. It is worth dwelling on this image for a moment. Vyāsa’s legs are “fittingly burly from bottom to top,” and “cause the person who worships him to become the same.”18 Sitting on a deerskin that shines with the “lovely sheen of sunlight,” Vyāsa possesses a miraculous hue.19 His “slender, soft, beautiful lotus belly” contains the whole universe.20 Nārāyaṇa exploits the ambiguous word division in the phrase brahma-su-sūtram to simultaneously tell us that Vyāsa’s chest appears white because of the upanayana thread (brahmasu sūtram) and that his heart is captivating because it holds the glorious aphorisms about brahman, that is, the Brahmasūtras (brahmasusūtra).21 His arms possess soft, ruddy hands that have the marks of Viṣṇu’s discus and conch.22 His neck has three auspicious lines, one for each of the Vedas he composed.23 Vyāsa’s face outshines the light of a thousand beams from a spotless moon, and the appearance of his teeth against his red lips “put to shame a string of new pearls glimmering on ruby facets.”24 His speech, likened to a infinite spring of freshwater, fills the “wells which are the questions posed by thousands of Brahmans.”25 The Tulasi leaf that sits upon Vyāsa’s ear whispers, “O Lord, please do not let the lotus and other flowers steal my position out of jealousy.”26 And after describing his eyebrows and forehead, Madhva thinks about Vyāsa’s miraculous body and its innumerable qualities:27

-

ucitāṁ gurutāṁ dadhat kramāc chuci tējasvi suvr̥ttam uttamambhajatō ’tra ca bhājayaty adō vibhujaṅghayugalaṁ sarūpatām

18“The Lord’s two legs, appearing fittingly burly from bottom to top, are pure, brilliant, well-made, and excellent. They cause the person who worships him to become the same/to attain mōkṣa.” The pun here is on sarūpatā being a stage of mōkṣa, on which reading the legs confer the appropriate gurutā according to one’s stage of enlightenment (cf. Br̥hadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 5.13.1–4 [ed. Limaye and Vadekar 1958: 262–263], which is echoed later in the Bhāgavatapurāṇa and elsewhere).

-

acalāsanayōgapaṭṭikā varakakṣyā sakr̥dāptam iṣṭadamparitō ’pi hariṁ sphuranty ahō aniśaṁ dhanyatamēti mē matiḥrucirēṇa varēṇa carmaṇā rucirājadyuticārurōciṣāparamōrunitambasaṅginā paramāścaryatayā virājyatē

19“A meditation cloth for steady sitting posture, which has the finest hems, shines from all sides upon Hari as Vyāsa, who gives whatever is desired even when approached once—that cloth, in my opinion, is the most praiseworthy thing. The resplendent deer skin upon which he sits, which has the lovely sheen of sunlight, makes him appear most miraculous.” Bāṇa used the term yōgapaṭṭaka several times in the Harṣacarita. It means both a meditation cloth and a forged royal document. In his edition of the text, P. V. Kane (1918: notes, 26) gives the following explanatory verse. From where it comes, I am not sure.

pr̥ṣṭhajānvōḥ samāyoge vastraṁ valayavad dr̥ḍhamparivēṣṭya yad ūrdhvajñus tiṣṭhēt tad yōgapaṭṭakam -

tanunimnasunābhiśōbhitē valibhē vārijanābha ādadhēpratanāv atisundarē mr̥dāv udarē ’smin jagadaṇḍamaṇḍalam

20“He has kept the sphere of the universe in this slender, soft, beautiful lotus belly, which has delicate folds, and which is adorned with a soft, deep navel.”

-

hr̥dayē kr̥tasajjanōdayē suviśālē vimalē manōharēubhayaṁ vahati trayīmayaṁ bhagavān brahmasusūtram uttamamasamē ’nadhikē susādhitē nijatātē ravirāśidīdhitipradadau trijagajjayadhvajaṁ vidhir ētad galasaṅgibhūṣaṇam

21“The lord holds the two best Vedic sūtras: One he wears on his broad chest, the other he holds in his expansive heart, which uplifts the righteous. In the case of the [upanayana] thread on Brahmans [brahmasu sūtra], his chest is white and beautiful, whereas in the case of the glorious aphorisms about brahman [i.e., the Brahmasūtra], his heart is pure and captivating. When Vyāsa proved [through his various compositions] that Viṣṇu is unequaled and unsurpassed, Brahmā gave him this ornament, the kaustubha gem, which hangs around his throat as a symbol of his conquest over the three worlds and which shines like a cluster of suns.” The word susūtra can be glossed as śōbhanam sūtram iti susūtram.

-

arivārijalakṣaṇōllasatsukumārārūṇapāṇipadmayōḥpr̥thupīvaravr̥ttahastayōr upamāṁ naiva labhāmahē ’nayōḥbhavatāṁ varatarkamudrayā dyati hastāgram abōdham īśituḥadhijānusamarpitaṁ paraṁ kr̥tabhūyōbhayabhaṅgamaṅgalam

22“I cannot find a comparison for these two arms, which have large, brawny, and round forearms, which have lotus-like hands that are soft, ruddy, and resplendent with the marks of Viṣṇu’s discus and conch. Through jñānamudrā, the fingers of one hand destroy the ignorance of devotees. The fingers of the other sit atop the knee, auspicious for their part in vanquishing tremendous fear.”

-

satataṁ galatā svataḥ śrutitritayēnēva nikāmam aṅkitaḥsuviḍambitakambur īkṣyatē vararēkhātrayavān guror galaḥ

23“I see Vyāsa’s neck, which, perfectly resembling a conch shell, has three auspicious lines; the neck, which is clearly marked [or numbered] by the three Vedas that issue forth [from his throat] eternally.”

-

sakalāstakalaṅkakālimasphuradinduprakarōruvibhramamadharīkurutē svaśōbhayā vadanaṁ dēvaśikhāmaṇēr idamaruṇāśmadalāntarōllasannavamuktāvalim asya lañjayēthasataḥ sitadantasantatiḥ paramaśrīr aruṇoṣṭharōciṣaḥ

24“By its own splendor, the face of Vyāsa—the crown jewel of the gods—outshines even the beautiful light from a thousand moon rays blazing brightly after the moon’s spots have been completely removed. Smiling and effulgent with red lips, Vyāsa has a row of the most beautiful white teeth that would put to shame a string of new pearls glimmering on ruby facets.”

-

dvijavr̥ndakr̥taṁ kutūhalād anuyōgāndhusahasram uttamamiyam ēkapadē sarasvatī śrutibhartuḥ paripūrayaty ahō

25“Amazing! With a single word, the Lord of Scripture’s riverine speech miraculously fills up thousands of well-like questions posed by scores of Brahmans.”

-

jalajāyatalōcanasya mām avalōkō ’yam upētya lālayankurutē parirabhya pūritaṁ bhuvanānandakarasmitānvitaḥupakarṇam amuṣya bhāsitā tulasī mantrayatīva lālitāmama nātha padaṁ na matsarāj jalajādyāni hareyur ity alam

26“I became fulfilled after this sportive gaze of Vyāsa—whose eyes are wide like lotus petals—fell to me and embraced me, the gaze accompanied by a smile that makes all sentient beings happy. It is as if the beloved Tulasi leaf that sits just above his ear mutters silently to itself—‘O Lord! Let not the lotus and other flowers steal my position out of jealousy.’”

-

vibhavābhibhavōdbhavādikaṁ bhuvanānāṁ bhuvanaprabhōr bhruvōḥanayōr api dabhravibhramāt sabhavāṁbhōjabhavātmanāṁ bhavēttrijagattilakālikāntarē tilakō ’yaṁ parabhāgam āptavānharinīlagirīndramastakasphuṭaśōṇōpalapaṅktisannibhaḥ

27“From the slightest quiver of the Lord of Creation’s eyebrows would result the destruction, maintenance, and birth of all existing things, which have as their nature Śiva and Brahmā. This tilaka—which is indistinguishable from a row of rubies shining resplendent atop a sapphire mountain—has attained eminence in the middle of the Ornament of the Three Worlds’ forehead.”

navam ambudharaṁ viḍambayad varavidyudvalayaṁ jagadgurōḥavalōkya kr̥tārthatām agāṁ sajaṭāmanḍalamanḍanaṁ vapuḥna ramāpi padāṅgulīlasannakhadhūrājadanantasadguṇāngaṇayēd gaṇayanty anārataṁ paramān kō ’sya parō guṇān vadētna kutūhalitā kutūhalaṁ tanum ēnām avalōkya sadgurōḥsanavāvaraṇāṇḍadarśinō gr̥habuddhyā mama niṣkutūhalam

I became completely satisfied upon seeing the Lord of the Worlds’ body, which, with its most precious, lightning-bright arm band, resembles a new raincloud, and is festooned with a matted knot of hair. Not even Lakṣmī, despite continuously counting, could keep track of the innumerable, sanctified qualities emanating from just the movement of the toenails of Vyāsa’s feet. Who could possibly describe his virtues?

Nārāyaṇa Paṇḍita, Śrīmadhvavijaya (ed. Gōvindācārya vv. 7.45–48)

Simile, metaphor, alliteration, pun, and other poetic devices are key to conjuring Vyāsa’s image in the minds of Nārāyaṇa’s readers. So, too, is the failure of poetic language. Twice Nārāyaṇa stresses that words fail to express Vyāsa’s true glory. Even Lakṣmī cannot fully enumerate the qualities of Vyāsa’s toenails, let alone the totality of his body. How could a poet? Yet later Mādhva poets nevertheless tried. Nārāyaṇa’s Vyāsastōtra is a precursor for later Vyāsa praise poems. In addition to Praising Vyāsa, Condemning the Apostates, several other Vyāsastōtras are attributed to Vādirāja, including Eight Verses to Vyāsa (Vyāsāṣṭaka) and Describing Vyāsa (Vyāsavarṇana). Simple but rich compositions, Eight Verses and Describing Vyāsa appear to have been written for popular consumption. Vādirāja says as much—“For those devotees who recite Eight Verses every day, there is no defeat for them anywhere.”28

-

28Vādirāja, Vyāsāṣṭaka, v. 9, p. 40:

vāsiṣṭhavaṁśatilakasya harēr manōjñaṁ dōṣaughakhaṇḍanaviśāradam aṣṭakaṁ yēdāsāḥ paṭhanty anudinaṁ bhuvi vādirājadhīsambhavaṁ paribhavō na diśāsu tēṣām28“For those devotees who recite Eight Verses every day, which pleases Hari (Vyāsa), the ornament of the Vāsiṣṭha Dynasty, which is famous for destroying a deluge of faults, and which is born from the intellect of Vādirāja himself—for those devotees, there is no defeat anywhere.”

Reciting Vādirāja’s stōtras in the sixteenth century would have entailed repeating banal tropes. Vyāsa is Viṣṇu. He is the infallible author of the Mahābhārata, Purāṇas, and the Brahmasūtras. He is dear to the gods, and he shares a special connection to Madhva. But these tropes provided a frame for deft poetic flourishes:

indrādidaivatahr̥dākhyacakōracandrāmandāṁśukalpaśubhajalpitapuṣpavr̥ndaḥvr̥ndārakāṅghryupalatōguṇaratnasāndrō mandāya mē phalatu kr̥ṣṇataruḥ phalaṁ drāk

May the black tree (kr̥ṣṇataru) that is Vyāsa

quickly yield its fruits to me, Vādirāja, unintelligent as I am—

that black tree whose dazzling, flower bunch–like arguments

are like moon rays that sate the Cakōra birds

we call the hearts of gods like Indra and others;

that black tree, which has small creepers at its feet that are the other gods,

and which is encrusted with gem-like qualities.Vādirāja, Vyāsāṣṭaka (1953, v. 4, p. 39)

Vādirāja seems to reserve his most creative flourishes for verses that connect Vyāsa’s body to his literary creations. In the image of the dark tree above, Vyāsa’s skin is likened to the night sky; his textual creations—the Mahābhārata, the Brahmasūtras, and the Purāṇas—are like the cool rays of the moon; and the hearts of the gods are like Cakora birds, who slake their thirst on Vyāsa’s textual moonbeams. Vādirāja indulges in a similar strategy of stacking body and text when bowing to Vyāsa’s feet:

vēdāntasūtrapavanōddhr̥tapañcavēdāmōdāṁśatōṣitasurarṣinarādibhēdāmbōdhāmbujātalasitāṁ sarasīm agāḍhāṁ śrīdāṁ śritō ’smi śukatātapadām akhēdām

I have taken refuge at the deep lake that is the feet of Vyāsa, father of Śuka;

the lake-like feet that give wealth,

are tireless,

are adorned with lotuses of knowledge,

and by which the various gods, sages, and men are satisfied

by just a whiff of the fragrance of the five Vedas,

which has been lifted aloft

by the breeze of the Vēdāntasūtras.Vādirāja, Vyāsavarṇana, v. 2, p. 39.

Both Nārāyaṇa and Vādirāja used poetry to produce an image of Vyāsa in the minds of readers and listeners. Perhaps this sort of poetic image production was tantamount to a “corpothetics” before the age of print. Like the modern mass-produced images of Hindu gods that Christopher Pinney has suggested entail a “desire to fuse image and beholder,” the poetic reproduction and appreciation of Vyāsa’s image in the sixteenth century was made possible through the listener’s or reader’s faculties of linguistic understanding and literary imagination, all of which, of course, belong to the “beholder” of the image.31

-

31Pinney (2004: 194). Sanskrit literary aesthetics never presumed the mind-body dichotomy that defined western aesthetic theory since at least Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, and so Pinney’s effort to coin a neologism to describe a long-standing fact of aesthetic theory in South Asia is somewhat misplaced.

Violating Vyāsa, Slandering Śiva

By the turn of the seventeenth century, a new form of incendiary ritual involving Vyāsa’s amputated arm appears to have emerged among some Vīraśaivas in northwestern Karnataka. Vādirāja’s Praising Vyāsa, Condemning the Apostates is the first writing that I know of to critique the practice of cutting Vyāsa’s arm. Most of the essay is concerned with clearing up confusions about who, precisely, Vyāsa speaks for as a raconteur of epic events. But the last verses suggest that Vādirāja directed the essay toward a generic Śaiva devotee—an “idiot”—who wants to cut Vyāsa’s arm not just notionally, it would seem, but in practice.

Praising Vyāsa consists of thirty-one verses in śloka meter. It has been published at least twice. There are no known commentaries, but a manuscript in Mysore has extensive marginal notes that function as a kind of commentary.32 Both the printed text and the Mysore manuscript end with a short colophon: “Vādirāja Yati has composed this praise poem to Vyāsa (vyāsastōtra) in the form of a critique of the apostates.”33 Vādirāja may have called the essay a vyāsastōtra. Or perhaps a later copyist or cataloguer supplied the title. In either case, it is worth thinking about what, exactly, makes Praising Vyāsa a stōtra.

-

32The marginalia are anonymous, but they appear to have been copied by the same scribe who copied the main text. It is not impossible that the marginal notes belong to Surōttama, who many believe to be Vādirāja’s brother. Surōttama commented on several of Vādirāja’s writings, including the Pāṣaṇḍakhaṇḍanavyāsastōtra’s companion text, the Pāṣaṇḍakhaṇḍana.

-

33Vādirāja’s Pāṣaṇḍakhaṇḍanavyāsastōtra (Rāmācārya 1911): iti śrīvādirājayatikr̥taṁ pāṣaṇḍakhaṇḍanaṁ vyāsastōtraṁ.

Some have suggested that stōtras are stylistically distinct. Yigal Bronner, for instance, understands stōtras as “relatively short works in verse, whose stanzas directly and repeatedly address a divinity in the vocative case.”34 Others have suggested that a stōtra’s profusion of vocatives are the linguistic outgrowth of far more profound orientation toward a subject of praise. Hamsa Stainton, for instance, suggests that stōtras possess a certain “vectorial” or directional quality that foregrounds the act of praise itself.35 Yet Praising Vyāsa requires that we tweak either definition. Vādirāja’s addressees are not gods or divinities, but “idiots” and “scoundrels.” Insults replace sweet vocatives. And the very title of the essay betrays a multi-vectoral devotionality in which opprobrium is not inimical to the act of supplication but is in fact vital to it.

The text has a simple structure. The first third argues against Vyāsantōḷ on the basis of narrative-criticism. Vādirāja argues that Vyāsa is a victim of wrongful punishment. As a reporter of epic events, the thinking goes, Vyāsa was simply conveying a statement Bhīṣma had made about Viṣṇu being the ultimate lord instead of Śiva. Vīraśaivas have mutilated the messenger. The second third of the text poses a set of hypotheticals about wrongful punishment, which is followed by an argument about the liṅga being a symbol of Śiva’s dismemberment. The first two sections give way to a description of the painted image of Vyāsa and a set of concluding verses that say any Śaiva who wants to cut Vyāsa’s arm ends up harming Śiva instead.

Vādirāja begins by describing a declaration Bhīṣma made in front of an assembly of learned men:

bhīṣmēṇa kāmyakavanē dharmarāja(ṁ) nr̥paṁ pratisatyaṁ satyam iti ślōkō bhujāv uddhr̥tya pīvarauuktaḥ kila sabhāmadhyē kathēyam akhilā sphuṭāśēṣadharmāścaryaparvadvitīyādhyāyamadhyagāatas tasya bhujāv ēva chēdyau yady asti pauruṣaṁvyāsas tu tāṁ kathāṁ granthē nibabandha paraṁ sudhīḥkiṁ yamaḥ pāpinaṁ hanyāt kiṁ vā pāpasya sākṣiṇaḥhr̥tā sītā rāvaṇēnēty uktē nahi jaṭāyuṣaḥśiraś cicchēda bhagavān rāmō rājīvalōcanaḥkiṁ tu bhāryāpahartāraṁ jaghāna yudhi rāvaṇaṁidaṁ nidarśanaṁ paśya māvivekē manaḥ kr̥thāḥuddhr̥tya śēṣadharmasthavākyāny api ca kānicitmandānām upakārāya darśayiṣyāmi tattvataḥ

Among the assemblymen in the Kāmyaka forest, Bhīṣma proclaimed the verse “this is the truth, this is the truth” to king Dharmarāja (Yudhiṣṭhira), brawny arms lifted high. This well-known tale is found in the second chapter of the Āścaryaparvan on śeṣadharma. Therefore, the heroic thing to do would have been to cut off Bhīṣma’s arm. Vyāsa, who is exceedingly learned, simply recorded that event in the Mahābhārata. Should Yama, the god of death, kill the sinner? Or should he kill the one who witnessed the sin? The lotus-eyed Rāma didn’t cut off Jaṭāyus’s head after he reported that Rāvaṇa abducted Sītā Rather, Rāma killed the kidnapper of his wife, Rāvaṇa, in battle. Take a look at the evidence! Don’t fix your mind on this stupidity. After quoting a few statements from the śeṣadharma section of the Mahābhārata to help the idiots, I will make you understand the verses as they really are.

Vādirāja, Pāṣaṇḍakhaṇḍanavyāsastōtra (Rāmācārya 1911, vv. 1–7a)

Vādirāja poses a peculiar genealogy of Vyāsantōḷ. By his account, cutting off Vyāsa’s arm is born from a misreading of the Harivaṁśa (the Āścaryaparvan of the Mahābhārata). Yet the verses he cites are not found in the Bhandarkar edition of the text or in its critical apparatus, and only one can be found in Madhva’s commentary on the Mahābhārata, which Vādirāja invokes approvingly in the next passage. According to Vādirāja, it was Bhīṣma who lifted his arm and declared, “this is the truth, this is the truth, again, this is the truth.” Vādirāja continues:

yudhiṣṭhiraḥ —pitāmaha mahāprajña sarvaśāstraviśāradakr̥ṣṇē dharmē ca mē bhaktir yathā syād dhi tathā vadabhīṣmaḥ —śr̥ṇu pāṇḍava vakṣyāmi haribhaktiṁ sudurlabhāṁśrōtṝṇām sarvapāpāghnīṁ vadatāṁ ca yudhiṣṭhirasatyaṁ satyaṁ punaḥ satyam uddhr̥tya bhujam ucyatēvēdaśāstrāt paraṁ nāsti na daivaṁ kēśavāt paraṁsatyaṁ vacmi hitaṁ vacmi sāraṁ vacmi punaḥ punaḥasārē khalu saṁsārē sāraṁ yad viṣṇupūjanaṁuddhr̥tya svabhujau bhīṣmaḥ śaśaṁsa kila saṁsadiēvaṁ cēd vyāsadēvasya kō ’parādhō vicārayaatō madhvamunēr vākyē bhāratajñaśikhāmaṇēḥuddhr̥taṁ bāhuyugulaṁ yathā bhavati vai tathābhīṣmācāryakr̥tasyōgraśapathasyānuvāditaṁyatra tad vai vyāsavacaḥ śr̥ṇu cēt tava yōjanātattatkr̥tyānuvaktā ca śāstrācāryō ’khilasya caaśēṣanigamōddhartā hartā duḥsamayasya camanaḥsaṁkalpamātrēṇa kurupāṇḍavasēnayōḥkartā satyavatīputrō vihartā munimaṇḍalērājasūyasya cārcāyaḥ sarpayāgasya ca prabhuḥkas tasya bhujayōś chēttā kiṁ vā tac chēdakāraṇambhramamūlā tataḥ sarvā kathāsīd vyāsavairiṇāmrajakadrōhatō bhikṣōḥ śūlārōpaṇavākyavatbhrāmakaṁ tasya śāstraṁ ca yatrētthaṁ samudīritam

Yudhiṣṭhira said: “O grandfather, great intellect, expert in all the sciences, teach me in such a way that I should be devoted to Kr̥ṣṇa and dharma.”

Bhīṣma replied: “Listen up, Yudhiṣṭhira. I’ll tell you about devotion to Viṣṇu, which is very difficult to get in this world, a devotion that destroys the sins of both listeners and speakers alike. This is the truth! This is the truth! Again, this is the truth! I proclaim this lifting my arm. There is no scripture superior to the Vedas. There is no god superior to Viṣṇu. I am telling you the truth. I am describing what is beneficial for you. I am telling you again and again the essence of everything. The one essential thing in this essence-less existence is worshiping Viṣṇu.”

Lifting his arms in the air, Bhīṣma proclaimed this in the assembly of kings. If this is the way it was, why fault Vyāsa? Think about it! This is why Madhva—the crest-jewel among those who know the Mahābhārata—wrote in his commentary on the Mahābhārata that just as Bhīṣma said this while raising his arms, Vyāsa recounted it in the same way (i.e., arms raised). If only you would pay attention to Vyāsa’s speech, then your sense of the passage would be that it is a retelling of the great vow taken by Bhīṣma. Vyāsa is the narrator of this or that person’s deeds in the epic and is the teacher of the whole Mahābhārata. He is the rescuer of the Vedas and destroyer of incorrect codes of conduct. By simply setting his mind to it, Vyāsa—the son of Satyavatī and who relishes being in the assembly of sages—creates the Kurus and Pāṇḍavas (in the minds of the reader) and presides over the Rājasūya, Arcā, and Sarpayāga rites. Who could cut off Vyāsa’s arms, and what is the purpose of doing so? Thus, the whole story about severing Vyāsa’s hand is, at its root, erroneous and belongs to those who hate him. This is like calling for a sage to be impaled on a spike for the crimes of a washman. And where a text prescribes cutting off Vyāsa’s arm, it does so to deceive whoever reads it.

ibid., vv. 7b–19.

After arguing that Vyāsa was simply relaying Bhīṣma’s sermon when he repeated the phrase, “this is the truth,” Vādirāja turns his attention to Śiva. If any god has been dismembered, Vādirāja claims, it is Śiva not Vyāsa. He cites a story from the Padma Purāṇa in which Śiva, who had been distracted while having sex with Pārvatī, snubs Bhr̥gu who then chops Śiva to pieces out of anger. All that remains is Śiva’s penis mid-coitus, which is symbolized by the liṅga that Vīraśaivas wear and worship. He writes:

nārīsaṁgamamattō ’sau yasmān mām avamanyatēyōniliṅgasvarūpaṁ hi tasmād asya bhaviṣyatiiti padmapurāṇōktaṁ bhr̥guśāpasya sāhasaṁpaśyantu pañcaśīrṣāṇi bhujānām ca catuṣṭayaṁdvau pādāv adaraṁ vakṣaḥ kaṭī cōrū ca dhūrjaṭēḥvichidya tatkṣaṇād ēva petuḥ kila mahītalēśiśnamātraṁ tūrvaritaṁ tac ca yōnyām nivēśitaṁatra pramāṇaṁ śaivānāṁ kaṇṭhē kaṇṭhē vilaṁbinīliṅgamālaiva yā nityaṁ karē vāmē prapūjyatēataḥ pādmōditakathā śaivānām api saṁmatā

In the Padma Purāṇa, the punishment of the curse of Bhr̥gu is relayed in the following way:

“Śiva, who was out of his mind because he was having sex with his wife, disrespected me (Bhr̥gu). Because of this, Śiva’s body will be reduced to his penis in Pārvatī’s vagina. Let everyone see that after Śiva’s five heads, his four arms, his two feet, stomach, chest, hips, and thighs are chopped off, they fall to the ground in an instant. Only his penis, which had entered the vagina, remained.”

The proof for this is that around Śaivas’ throats dangle a necklace of Śiva’s penis, which they worship with the left hand. Thus, the Śaivas, too, agree with me on this story from the Padma Purāṇa.

ibid., vv. 20–24.

The salacious provocation gives way to reverential praise, where Vādirāja invokes the “knowledge-giving image of Vyāsa” as painted on walls by artists and described in mantra texts:

hastadvayavatī ramyajaṭāmaṇḍalamaṇḍitāpadmapādā śyāmavarṇā lasatkr̥ṣṇājinōjjvalāmandasmitā candramukhī bimbōṣṭhī paṅkajēkṣaṇākundakuḍmaladantābhā sāndrakuntalasaṅkulākandarpakōṭisadr̥śī saundaryāṁbudhimandirāvandārūṇām abhayadā vandyamānāsurair naraiḥadyāpi pūjyatē vyāsapratimā jñānadāyinīcitrakair likhyate bhittau mantraśāstreṣu varṇyate

Even today, the knowledge-giving image of Vyāsa is painted on walls by artists and is described in various mantra texts—

the image, which shows Vyāsa as having two hands;

as being lustrous with beautiful hair;

as having dark, lotus-like feet;

as luminous from the radiant antelope skin he sits on;

as smiling with happiness;

as having a moon-like face with lips like the bimba fruit;

as having lotus-like eyes and teeth like budding jasmine flowers;

as having thick hair;

the image of Vyāsa is like a crore of gods of love;

is the object of devotion for those who worship beauty;

it gives fearlessness to all those who prostrate;

and it is worshiped by both gods and humans alike.Vādirāja, Pāṣaṇḍakhaṇḍanavyāsastōtra (Rāmācārya 1911, vv. 25–28)

Vādirāja concludes by writing:

atō vyāsabhujacchēdam āśāsānasya durmatēḥsvadairvasarvagātrāṇāṁ chēdaḥ khēdakarō ’bhavattadvr̥ddhim icchatō mūlachēdō ’bhūt tava durjanayadvyāsāya druhyatas te śivadrōhō ’bhavad dhruvaḥvivādaparihārāya kathēyaṁ grathitā kilayatinā vādirājēna vyāsakaiṅkaryakāmināiti śrīvādirājayatikr̥taṁ pāṣaṇḍakhaṇḍanaṁ vyāsastōtraṁ

It follows, then, that the idiot who is longing to amputate Vyāsa’s arm is tormented instead by cutting off all of your own god’s limbs. Hey, loser! You wanted interest on your capital, but you ended up losing your capital instead. By violating Vyāsa, you ended up slandering Śiva. Desiring servitude to Vyāsa, I have composed this story to solve the controversy of his arm.

Vādirāja, Pāṣaṇḍakhaṇḍanavyāsastōtra (Rāmācārya 1911, vv. 29–31)

Unlike other Vyāsa stōtras, Praising Vyāsa combines perfunctory textual arguments with declarations about Vyāsa’s painted image not to construct a new image of Vyāsa in the minds of readers, but to restore an image under threat. The textual and visual arguments about Vyāsa’s body amount to two intersecting axes for managing the volatility of Vyāsa’s representation. The close connection between image and text suggests that the problem of cutting Vyāsa’s arm was not simply an act of iconoclasm, but also a form of textoclasm in which the Mahābhārata and its interpretive methods were wounded alongside Vyāsa’s body.

Piety and Paralysis at Śiva’s Doorstep

I want to begin a provisional genealogy of Vyāsantōḷ by looking at an episode in the Skanda Purāṇa, in which Vyāsa, who is depicted as a zealous devotee of Viṣṇu, was paralyzed and convinced of Śiva’s supremacy. That Vyāsa was the target of a type of forced conversion is unsurprising. Peter Bisschop has recently argued that the Skanda Purāṇa emerged in part as a Śaiva rejoinder to the Vaiṣṇavization of the Mahābhārata, and so any reappropriation of the epic would inevitably involve Vyāsa.36 In an episode in the Kāśīkhaṇḍa, Vyāsa is depicted as a haughty Vaiṣṇava who wandered around haranguing sages about the glories of Hari. Once in the Naimiṣa Forest, Vyāsa found himself standing before thousands of ash-smeared Śaivas. He lifted a finger and indulged in a sanctimonious sermon:

-

36In Bisschop’s words, the Skanda Purāṇa is where Vyāsa became “a dedicated Pāśupata adept” (Bisschop 2021: 49).

parinirmathya vāgjālaṁ suniścityāsakr̥d bahuidam ēkaṁ parijñātaṁ sēvyaḥ sarvēśvarō hariḥvēdē rāmāyaṇē caiva purāṇēṣu ca bhāratēādimadhyāvasānēṣu harir ēkō ’tra nāparaḥsatyaṁ satyaṁ trisatyaṁ punaḥ satyaṁ na mr̥ṣā punaḥna vēdād aparaṁ śāstraṁ na dēvō ’cyutataḥ paraḥlakṣmīśaḥ sarvadō ’nānyo lakṣṁīśō ’py apavargadaḥēka ēva hi lakṣṁīśas tatō ’dhyēyō na cāparaḥbhuktēr muktēr ihānyatra nānyō dātā janārdanāttasmāc caturbhujō nityaṁ sēvanīyaḥ sukhēpsubhiḥvihāya kēśavād anyaṁ yē sēvantē ’lpamēdhasaḥsaṁsāracakrē gahane tē viśanti punaḥ punaḥēka ēva hi sarvēśō hr̥ṣīkēśaḥ parāt paraḥtaṁ sēvamānaḥ satataṁ sēvyas trijagatāṁ bhavētēkō dharmapradō viṣṇus tv ēkō bahvarthadō hariḥēkaḥ kāmapradaś cakrī tv ēkō mōkṣapradō ’cyutaḥśārṅgiṇaṁ yē parityajya dēvam anyam upāsatētē sadbhiś ca bahiṣkāryā vēdahīnā yathā dvijāḥ

After churning a vast ocean of words, and after becoming perfectly sure of their meaning time and again, I’ve come to know this one thing—Hari is the one who should be worshiped. Hari is the lord of all. From beginning to end, the Vedas, Rāmāyaṇa, Purāṇas, and Mahābhārata convey only Hari and no one else. This is the truth! This is the truth! Again, this is the truth! A triple oath. It’s not wrong to say that there is no scripture greater than the Vedas, no god greater than Hari. No one but the Lord of Lakṣmī is the giver of all, and no one but Lakṣmī is the giver of heaven. Because the Lord of Lakṣmī is the one and only, it follows that he should be worshiped and no one else. No one but Janārdana gives enjoyment in this world and liberation hereafter. Thus, those who want happiness should always serve Viṣṇu. Having abandoned him, the stupid people who worship another god consign themselves again and again to the mysterious cycle of saṁsāra. Indeed, there is only one lord of all. Hr̥ṣīkēśa is the best of the best. Whoever attends to him would themselves be the object of constant worship of the three worlds. Only Viṣṇu is the giver of dharma. Only Hari is the giver of riches. Only the Discus-Bearer is the giver of pleasure. And only Acyuta is the giver of liberation. Those who forsake the Archer and worship another god should be abandoned by the virtuous, like a Dvija who has lost the Vedas.

Skāṇḍapurāṇīyakāśīkhaṇḍa (Śrēṣṭhin 1908, vv. 95.11–19, fol. 351v)

The Śaiva sages of the Naimiṣa Forest revered Vyāsa for arranging the Vedas and authoring the Mahābhārata, but his homily made them agitated. The sages spoke up: “The people here don’t trust what you have just argued with your finger raised confidently. But we would trust you if you proclaim it in front of Śiva in Benares.”37 Annoyed, Vyāsa set off for Śiva’s city with his entourage. Their time in Benares began wondrously: Vyāsa bathed at the city’s ghats and performed rites for Viṣṇu. Conch-calls announced his presence. Devotees adorned him with fresh garlands of Tulasi. And he sang the lord’s many names in the streets. It was in the buoyant din of devotion that Vyāsa and his followers danced their way to Śiva’s doorstep at the Viśveśa Temple. They sang some more, and when the music stopped, Vyāsa stood there among his students. “He lifted his right arm,” the passage reads, “and he loudly recited the Naimiṣa sermon again, this time as if it were song—‘After churning a vast ocean of words, and after becoming perfectly sure of their meaning time and again, I’ve come to know this one thing—Hari is the one who should be worshiped, Hari is the lord of all.’”38

-

37Skāṇḍapurāṇīyakāśīkhaṇḍa (Śrēṣṭhin 1908, vv. 95.23–25, foll. 351v–352r):

bhavatā yat pratijñātaṁ niścityōtkṣipya tarjanīmasmin māṇavakās tatra pariśraddadhatē na hipratijñātasya vacasas tava śraddhā bhavēt tadāyadānandavanē śaṁbhōḥ pratijānāsi vai vacaḥ -

38Skāṇḍapurāṇīyakāśīkhaṇḍa (Śrēṣṭhin 1908 v. 95.44, fol. 352r):

punar ūrdhvaṁ bhujaṁ kr̥tvā dakṣiṇaṁ śiṣyamadhyagaḥpunaḥ papāṭha tān ēva ślōkān gāyann ivōccakaiḥparinirmathya vāgjalāṁ suniścityāsakr̥d bahuidam ēkaṁ parijñātaṁ sēvyaḥ sarvēśvarō hariḥ

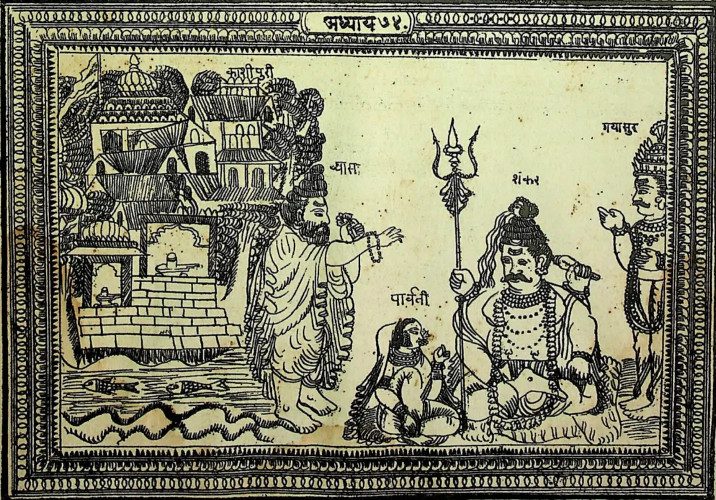

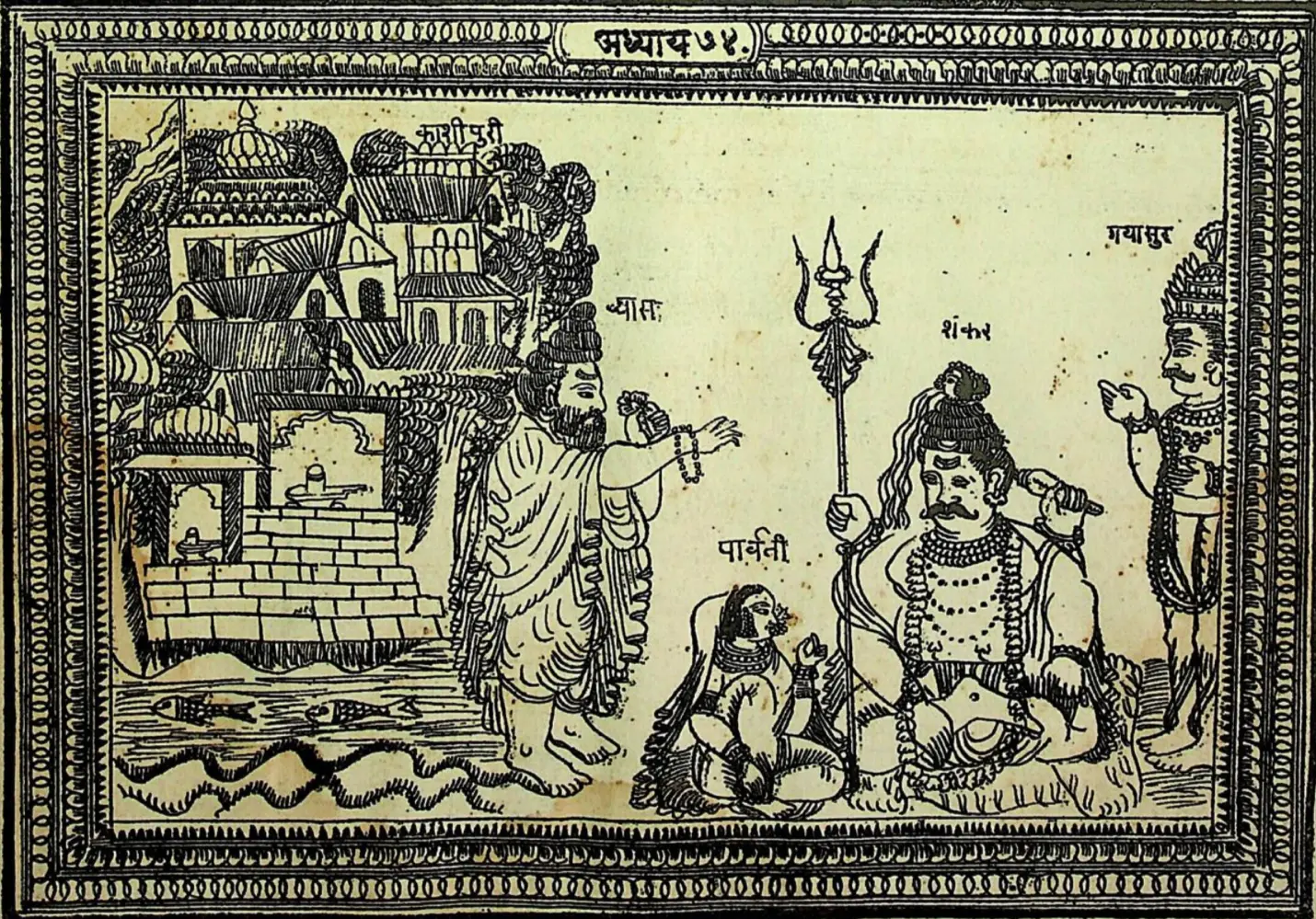

Vyāsa the pious provocateur became a chapter frontispiece for a Marathi translation of the Kāśīkhaṇḍa published in 1881. The lithograph shows Vyāsa standing in front of Śiva and Pārvatī, right arm lifted as he pronounces Viṣṇu the lord of all. In the Marathi edition, Gayāsura is the one who points his finger and curses Vyāsa. The more popular telling has Śiva’s attendee Nandin doing the cursing. In both, Vyāsa’s arm became stiff and his voice faltered mid-sermon. For all the dancing and singing, Vyāsa could never quite summon Viṣṇu. But in the silent paralysis of Nandin’s curse, Viṣṇu finally appeared. Rather than praise Vyāsa for his devotion, however, Viṣṇu admonished him. “O Vyāsa! You’ve committed a serious sin. Even I’m terrified by your offense.”39 Viṣṇu explains:

-

39Skāṇḍapurāṇīyakāśīkhaṇḍa (1908), vss. 95.48b–49a, fol. 352v:

aparādhaṁ mahac cātra bhavatā vyāsa niścitamtavaitad aparādhēna bhītir mē ’pi mahattarā

ēka ēva hi viśvēśō dvitīyō nāsti kaścanatatprasādād ahaṁ cakrī lakṣmīśas tatprabhāvataḥtrailōkyarakṣāsāmārthyaṁ dattaṁ tēnaiva śambhunātadbhaktyā paramaiśvaryaṁ mayā labdhaṁ varāt tataḥidānīm stuhi śaṁbhuṁ yadi mē śubham icchasi

Śiva is the one true lord of the universe. There’s no second. His grace makes me the discus bearer, his power makes me Lakṣmī’s husband. It’s Śambhu who gives me the ability to protect the three worlds. It’s only by devotion to Śiva that he granted me divine status as a boon. If you desire my welfare, praise Śambhu.

Skāṇḍapurāṇīyakāśīkhaṇḍa (Śrēṣṭhin 1908, vv. 95.49b–51, fol. 352v)

Still speechless, Vyāsa gestured for Viṣṇu to restore his speech. Viṣṇu obliged, and Vyāsa (arm still paralyzed) praised Śiva as the ultimate lord with eight verses (a Vyāsāṣṭaka of a different kind).

Paralysis was only the beginning of Vyāsa’s difficulties in Kāśī. Hunger, desperation, and, in some tellings, exile would await him after Nandin lifted the curse.40 Yet of all Vyāsa’s travails, his paralyzed arm proved an especially potent subject of poetic focus. The Telugu poet Śrīnātha elaborated on this episode in his Kāśīkhaṇḍamu, and it appears to have migrated out of the Purāṇas altogether and circulated as a standalone work.41 For instance, a short manuscript at the Rajasthan Oriental Research Institute in Jodhpur titled Praising the Paralysis of Vyāsa’s Arm (Vyāsabhujastambhanastōtra) recounts Vyāsa’s paralysis in Kāśī in the form of praise poem.42

-

40Skanda goes on to narrate the famous episode of Vyāsa’s hunger in Kāśī. The fourteenth-century Vīraśaiva and Telugu poet Śrīkaṇṭha used this episode in his Bhīmēśvarakhaṇḍamu to foreground Vyāsa’s exile from Kāśī and his arrival at Dakṣarāma. See Narayana Rao and Shulman (2012: 76–81).

-

41Śrīnātha, Kāśīkhaṇḍamu 7.103–110 in Narayana Rao and Roghair (1990: 281, n. 29).

-

42Vyāsabhujastambhastōtra (1984), p. 266.

In both the Skanda Purāṇa and Praising Vyāsa, Vyāsa lifts his arm and proclaims his triple oath about Viṣṇu’s supremacy—“This is the truth! This is the truth! Again, this is the truth!” In the Skanda Purāṇa, Vyāsa’s declaration is his own, whereas in Praising Vyāsa it is Bhīṣma’s. Vādirāja does not mention what happens to Vyāsa’s voice, but the Skanda Purāṇa positions aphonia alongside monoplegia as connected afflictions. Vyāsa’s arm is simply an extension of a pious speech act, and its uplifted position a gesture of steadfast devotion. It is the arm’s connection to Vyāsa’s Viṣṇu worship that transformed it into a location for, and an eventual symbol of, the rejection of the belief of Viṣṇu's supremacy over Śiva.

The arm as a site of divine intervention is a well-worn trope. Vyāsa’s paralysis in Kāśī mirrors an episode in the Drōṇaparvan of the Mahābhārata, where the infant Śiva paralyzed Indra’s uplifted arm just as Indra was about to kill him with a lightning bolt.43 The Śivadharmōttara (ca. seventh century CE ), for instance, describes a variety of divine afflictions: the Sun has leprosy, Varuṇa has dropsy, Pūṣan is missing teeth, Soma has consumption, Dakṣa Prajāpati has a fever, and Indra has a paralyzed arm (bhujastambha). The Śivadharmōttara and the later Tamil Civatarumōttaram (ca. sixteenth century CE ) do not specify Śiva’s role in Indra’s paralysis, but the Taṇikaipurāṇam (ca. eighteenth century CE ) clarifies that it was indeed Śiva who brought on these afflictions.44

The paralysis of Indra’s arm in the Mahābhārata and Śivadharmōttara may have provided a template for the story of Vyāsa’s paralysis in Kāśī. Amputation is medically distinct from paralysis, but their narrative forms are distinguished only by degrees of permanence. The severing of Vyāsa’s arm is different from the paralysis of Vyāsa’s arm because it is a permanent intervention in a pious gesture instead of a temporary one. Amputation is perhaps best understood as an inevitable amplification of the kind of bodily interventions Śiva had long been depicted as exercising over other gods. The drift from paralysis to amputation is difficult to track, but it is evident in faint traces in Vīraśaiva writings from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, where Purāṇic accounts of Vyāsa’s paralysis became a reference point for prescribed interventions against Śiva’s naysayers and critics.

The ninth chapter of the Siddhāntaśikhāmaṇi of Śivayōgin (ca. mid-thirteenth century CE ), for instance, enumerates a pious Śaiva’s ideal conduct and their salvific rewards.45 Many dictates concern matters of conduct, almsgiving, and ritual purity. But a handful of others promote a punitive strategy against Śiva’s enemy’s—“one should be ready to martyr themselves to protect a liṅga and its devotees from destruction,” reads one verse.46 Another reads:

-

45Here I take M. R. Sakhare’s dates. See Sakhare (1942: 370).

-

46Śivayōgin, Siddhāntaśikhāmaṇi (Śivakumāra 2015, v. 9.34–35).

If you see someone criticizing Śiva, then you should hurt them (ghātayēt), or (in the least) you should curse them (śapēt). If you can’t do either, then you should turn from that place and go away.47

-

47Śivayōgin, Siddhāntaśikhāmaṇi (Śivakumāra 2015, v. 9.36). The causative imperative verb ghātayēt, from the root han in the sense of violence (hiṁsā) or going (gati), is perhaps intentionally underdefined.

For Maritōṇṭadārya, a commentator who lived between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, “to hurt” Śiva’s enemies was an insufficiently harsh reading of the verb ghātayēt.48 Śiva’s enemies should be cursed or killed, and to support this, Maritōṇṭadārya classifies the verse under the heading “The Conduct of Vīrabhadra and Nandin” (vīrabhadrācāranandikēśvarācāra).49 The reference is clear: In the eighty-ninth chapter of the Skanda Purāṇa, just a few chapters before Vyāsa’s paralysis, Dakṣa hosted an enormous sacrifice but did not invite Śiva. Worried that Dakṣa’s irreverence will spread to others, Śiva commanded Vīrabhadra to destroy the sacrificial grounds. The result was a bloodbath. Vīrabhadra and his gang destroyed the sacrificial pavilion. They dug up the altars, drank the oblations, crushed the utensils, and devoured the sacrificial animals. Drunk on power, they massacred those who attempted to flee—they castrated Vāyu and cut off Sarasvatī’s nose. Aditi lost his lips, Aryaman his arms, Agni his tongue. Viṣṇu—the source of Dakṣa’s strength and the recipient of the sacrifice—was nearly killed, but a voice from the heavens intervened just as Vīrabhadra was about to sink a trident into his chest. Vīrabhadra redirected his rage to Dakṣa, whom he swiftly bludgeoned to death with bare knuckles. Dakṣa’s demise was hardly the end of the butchery. Those who had not yet fled were methodically dismembered and hung from the sacrificial post.

-

48Tōṇṭada in old Kannada means “garden.” Tiziana Ripepi (1997) has argued that as a name or title, Tōṇṭada only came into circulation after the Vijayanagara ruler Virūpākṣa, whose guru was given the title Tōṇṭada Siddhaliṅgēśvara. Ripepi disagrees with Jan Gonda, who dates Maritōṇṭadārya to the fifteenth century. She suggests instead that he lived in the eighteenth century.

-

49In some recensions the heading reads, “The Conduct of Vīrabhadra and Basavēśvara” (vīrabhadrācārabasavēśvarācāra), which pairs with the mandate to turn away and leave if one is not able to curse or beat, which is an homage to a story of Basava leaving Kalyāṇa after the city was overrun and looted by marauding anti-Śaivas.

Maritōṇṭadārya seems to have had Vīrabhadra’s murderous rage in mind when glossing the verb ghātayēt as “the conduct of Vīrabhadra,” that is, “mutilating and murdering Śiva’s enemies.” Perhaps Maritōṇṭadārya found the end of the chapter, where Śiva, dismayed by Vīrabhadra’s savagery, brought his victims back to life, an unsatisfactory coda to apostasy, for he never recommends taking pity on those who speak ill against Śiva or his followers. Or perhaps Śiva’s mercy for those who were righteously slain was precisely what made violence palatable, even if only notionally. Regardless, Maritōṇṭadārya linked the second verbal action—“should curse” (śapēt)—to the story of Nandin and Vyāsa’s arm just a few chapters later, thus presenting butchery and bodily maiming as a logical concatenation of cursing.50

-

50For Śivayōgin, cursing and beating are complimentary responses to critics, but there’s no reason to suspect that he had the Skanda Purāṇa in mind when writing the verse.

Like most scriptural dictates, Maritōṇṭadārya’s prescriptions mapped unevenly onto life on the ground. Critics of Vīraśaivism like Vādirāja Tīrtha—who was historically and regionally proximate to Maritōṇṭadārya—were, so far as we know, never cursed, beaten, or tortured for their dissenting views, despite having brushed shoulders with south India’s most powerful Vīraśaiva warlords. In fact, the opposite was true. The Vīraśaiva kings at Keḷadi and Ikkeri, erstwhile vassals of Vijayanagara who controlled what is now western Karnataka, Goa, and the Kanara coasts, lavished Vādirāja and other putative critics of Vīraśaivism, including Jains and Muslims, with royal largesse.51 Perhaps, then, cutting Vyāsa’s arm was realpolitik, a calculated displacement of a perilous, even impossible, command onto a symbolically potent figure. Why waste energy on an ordinary slanderer when Vyāsa, “the paragon of Vedic Brahmanical r̥ṣi-hood,” to borrow Christopher Minkowski’s words, is available instead?52

Conclusion: Contesting Vyāsantōḷ in Colonial Courts

Vādirāja, Śivayōgin, and Maritōṇṭadārya (to say nothing of Purāṇas and epics) leave a crucial question unanswered: how was Vyāsantōḷ practiced in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries? Vādirāja argues against the practice on textual grounds. Its proponents have confused or exploited the labyrinthine dialogues and frame stories of the Mahābhārata and pilloried Vyāsa for a declaration that was not his. By the early nineteenth century, however, when the Vīraśaivas of Kolhapur were preparing Vyāsa’s arm for display in the city’s streets, Vyāsantōḷ had spilled well beyond the written page. What follows is hardly an exhaustive account of this transition, but I want to conclude by way of a provisional sketch of Vyāsantōḷ’s juridical life in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

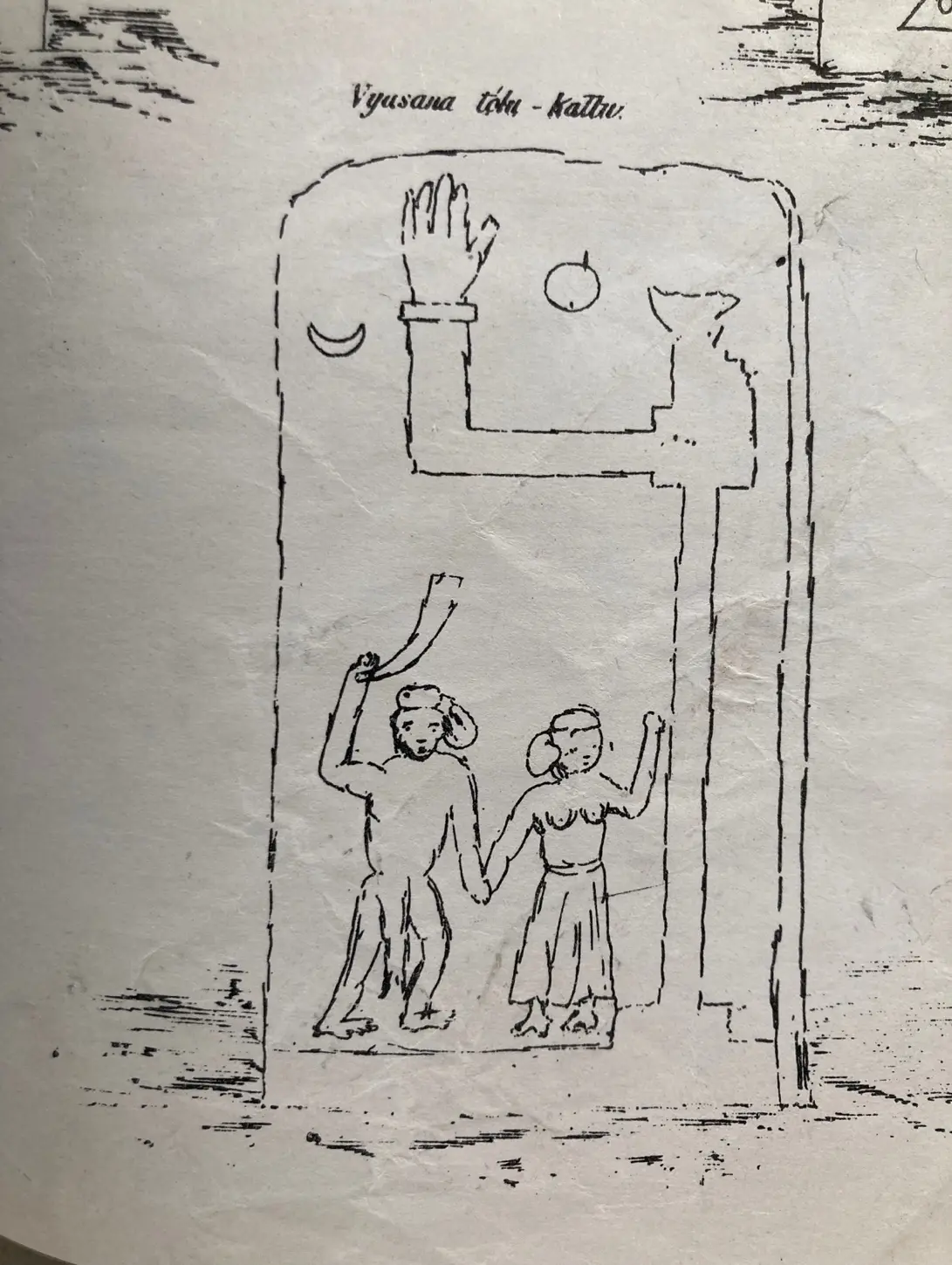

Vādirāja does not treat Vyāsantōḷ as a processional practice, but epigraphic evidence suggests that Vīraśaivas may have incorporated Vyāsa’s arm into a fixed pillar or mobile pole adorned with a flag of Nandin and other decorations (aptly called the Nandikamba) sometime before the nineteenth century. In the early 1870s, Colonel John Mackenzie made a sketch of a stone tablet in Mysore that depicts a man and woman at the base of a fixed pillar mounted with a large arm. The woman touches the pillar while the man next to her brandishes a scythe or sword. Mackenzie labeled the image Vyāsana tōḷu-kattu—“cutting off Vyāsa’s arm.”

The pillar on the tablet appears to be fixed, perhaps even made of stone, but it nevertheless resembles the kind of objects that were vigorously litigated in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Processional Nandikambas were made of bamboo and festooned with streamers, bells, brass globes, and, before it was outlawed, an effigy of Vyāsa’s arm and Nandin’s horn (nandikōḍu). Even today, Vīraśaivas parade an armless Nandikamba through the streets of villages and towns in northern Karnataka and southern Maharashtra.

A comprehensive study of Vyāsantōḷ’s path through District and High Courts warrants a separate study and is beyond the scope of this article. What I present here is selective and sketchy, consisting mostly of cases presented before the Bombay High Court in the early and mid-twentieth century. A richer story will surely emerge from a close study of court archives, judge’s notes, case records, private collections, and local newspapers. But even a cursory examination of the available legal material shows how the story of Vyāsantōḷ in colonial India is really a story about the definition of religion and its place in public life.

It is unclear precisely when, and through what legal pathways, Vyāsantōḷ became a subject of litigation, but records attest to district-level courts in the Deccan hearing civil cases in 1881 and probably earlier.53 Gazetteers and other records suggest that Vyāsantōḷ was unevenly practiced throughout the Deccan and that no discernible consensus had emerged about its legal standing before the first decades of the twentieth century, after which a series of high-profile cases wound their way to the Bombay High Court and tested settled decisions about religious processions and more technical matters of procedure.

In July of 1910, Lingayats in Athani, a small town in the Bijapur District of the erstwhile Bombay Presidency, petitioned the Collector of Belgaum to approve a Vyāsantōḷ procession planned for September 20. Like the Kolhapur procession a year later, they hoped to commemorate the arrival of a prominent monastic leader. Similar events on the Kanara coast had been approved despite resistance from local Brahmans. The Vīraśaivas of Athani informed Collector B. A. Brenson of these earlier processions. After a month or so of deliberation, Brenson approved the Lingayats’ request, albeit with clear instructions for where and how the procession should take place. Brenson wrote:

I therefore allow the Lingayats of Athani to hold a Vyāsantōḷ procession after the termination of the Ganesh festival. The procession will be allowed to take place in Athani town on the 20th September 1910, between the hours of 8 and 10 AM. It will enter the town at the Siddheshwar Gate, pass through the Aditwar Peth, the road connecting the latter with the Buddhwar Peth, and then down the Buddhwar Peth to the Gachin Math, where it will terminate at 10 AM. In this quarter of the town the residents are nearly all Lingayats. The Police Sub-Inspector will conduct the procession with a sufficient force to prevent any possible disturbance.

Pandurang Shidrao Gumaste Patil and other “Brahmans and non-Lingayats” appealed Brenson’s decision to M. C. Gibbs, Commissioner of the Southern Division. In a fragile victory for the Lingayats, Gibb’s declared on the 15th of September—four days before they were due to take to the streets—that Brenson’s decision was sound and that Vyāsantōḷ could take place. In a bid to halt the procession, Patil and the others filed an ex-parte application to the Bombay High Court. The Times of India reported that the justices, aware of scheduled police presence and the potential for unrest, were “reluctant to grant an order at the eleventh hour on an ex-parte application.” Yet the court succumbed to the situation and halted the procession until the “matter could be decided on merits.”54 The Lingayats of Athani would never march.

While reporting on the case, the Times of India explained Vyāsantōḷ to its educated, Anglophone readership:

The word “Vyasantol” literally meant the “arm of Vyas.” It was carried in procession on the top of a long pole in pursuance of a legend that Vyas, the composer of the Mahabharat epic and the other Hindu Puranic Shastras, was a great devotee of Vishnu in preference to Shiva. The arm which he had raised in devotion to Vishnu was therefore lopped off by a devotee of Shiva. In commemoration of this episode the arm was carried in public procession by the Lingayats who proposed themselves to be the ardent devotees of Shiva. The Brahman applicants on the other hand averred that this processional conveyance of the lopped limb of a sage man and sacred person like the muni Vyas, whom they held in considerable veneration was insulting, offensive, and revolting to their religious sentiments.

Despite being “revolting” to the “religious sentiments” of some, Vyāsantōḷ was never litigated on the basis of blasphemy law. The case before the Court concerned the right of religious procession and the authority of a District Magistrate to approve and oversee it. On October 14, the Bombay High Court ruled against Patil and the Brahman applicants, citing earlier cases that protected religious procession in public streets, including a judgment the court had issued just months earlier about a Lingayat parade in Deshnur (a controversy involving an automobile).55

-

55The cases are Sadagopachariar v. A. Rama Rao (1902), which was followed in Baslingappa Parappa Chedachal v. Dharmappa Basappa Chedachal (1910).

Newspapers played an important role both in bringing Vyāsantōḷ to a wider readership and in amplifying misinformation.56 A year after the Athani court case, the Times of India reported from so-called “vernacular sources” about a marauding band of Lingayats in Bagalkot, a small town in the Bijapur District. In addition to parading Vyāsa’s arm through the town’s streets, the Times reported, the Lingayats “defiled” the town’s Viṭṭhala temple, carried their guru’s palanquin “cross-wise” through the streets (an honor evidently restricted to Brahmans), and “committed on the Brahman residents numerous and unprovoked assaults.” The story was not true. The Times ran a brief press report on November 9 titled “Disturbance at Bagalkot” clarifying that Vyāsa’s arm had in fact not been paraded, that Lingayats had every right to parade their guru “cross-wise,” and that “the few individuals who did receive injuries seem to have provoked them (the Lingayats) by wantonly meddling with a lawful procession.”57

-

56See for instance a piece titled “Behind the Indian Veil: Faiths and Feuds” (Times of India, November 1910). The anonymous author named “an Indian” suggests that it was Virabhadra who cut off Vyāsa’s arm.

After the Bombay High Court dismissed the Athani Brahman’s ex parte application in October 1910 and sent Vyāsantōḷ back to lower civil courts, an atmosphere of legal ambiguity seems to have provided an opening for Vīraśaivas elsewhere in the Deccan to hold their own Vyāsantōḷ processions. Rajarshi Shahu—the Maharaj of Kolhapur who approved the parade in May 1911 and promised his marching band to boot—cited the Athani case as a reason for allowing the procession to proceed. But this favorable ambiguity would be short lived. On May 6, 191, just a week before the procession was due to take place in Kolhapur, Government Resolution no. 2658 was passed, which not only banned Vyāsantōḷ in Athani, but in the District of Belgaum “for all time.”58 The Lingayats of Athani swiftly sued.

A lengthy appeals process in lower courts meant that the Bombay High Court would not decide another case on Vyāsantōḷ until 1916. Dundappa Mallappa Sigandhi and Others v. Secretary of State for India and Others would prove a more complex and consequential case than the ex parte application of 1910. Having done considerable research, the judges (one of whom presided over the 1910 case) wrote that Vyāsantōḷ had been the subject of acrimonious litigation and civil conflict for more than a century and that a dispute about the right to parade Vyāsa’s arm had “always existed.”59 They specified that it was “Vaishnavite Brahmans” who were “most directly aggrieved,” but that Śaiva Brahmans and “non-Lingayat Hindus” sympathize with an “agitation against the procession.”60

Despite Vyāsantōḷ being an “obnoxious” and “unbecoming ceremony,” according to the defendants’ council, Vyāsantōḷ appeared to be on firm legal footing for two reasons: First, the way in which the Government Resolution had been upheld in lower courts was illegal (the details of which need not be dealt with here).61 Second, religious procession was a right that had been secured some years earlier by the Bombay High Court itself. The judges ruled in favor of the Lingayats once again.

-

61It had been upheld on the basis of the District Police Act (Bom. Act IV of 1890), which, the defendants argued, allowed the Government not to “prohibit” Vyāsantōḷ per se, but to deny future applications for its procession in perpetuity across the whole district.

Two cases decided by the Bombay High Court secured the right to religious procession. The first, Sadagopachariar v. A. Rama Rao (1907), concerned a century-long dispute between Vadakalai and Tenkalai Vaiṣṇavas over the use of streets around the Devanatha Swamy Temple in Thiruvanthipuram and its adjoining shrine dedicated to Vedānta Deśika, an important Vadakalai guru. After a century of legal wrangling, the Court ruled in 1907 that the public have a right to use city streets, even those adjoining prominent temples.62 The second case, which involved the use of automobiles in Lingayat processions, pushed the Court to clarify its position further: “every member of the public and every sect has a right to use the public streets in a lawful manner and it lies on those who would restrain him or it to show some law or custom having the force of law abrogating the privilege.”63

-

62In 1807, Tenkalais in Thiruvanthipuram sued Vadakalais for having been prevented from installing an image of a Tenkalai guru in the Devanatha Swamy Temple. The Tenkalais lost the suit but installed the image in a nearby house and began parading it in the streets around the temple. The Vadakalais sued in response, alleging that the streets around the temple were originally the property of Vadakalais who permitted the construction of houses on the condition that no “alien deity” be worshiped in them or processed on nearby streets. The court consulted a handful of sympathetic pandits who, the 1907 judges remark, based their decision “not so much on legal grounds as on precepts relating to ritual and ceremonial observances to be found in the ancient treatises on such subjects.” The Vadakalais won their case but there were numerous suits and countersuits until 1886, when the Magistrate of the Southern Arcot District refused to prohibit the public procession of Tenkalai images. Vadakalais lost on appeal and then brought the case to the Bombay High Court. The Court determined that there was no evidence attesting to the streets surrounding the temple belonging to Vadakalais. To the contrary, the streets belonged to the public under Madras Act No. V of 1884. See Baslingappa Parappa Chedachal v. Dharmappa Basappa Chedachal (1910).

-

63Baslingappa Parappa Chedachal v. Dharmappa Basappa Chedachal (1910).

Despite these safeguards, the courts never distinguished a “religious” procession from a non-religious one, nor had it specified whether laws protecting religious processions extended to others. This ambiguity laid the groundwork for a strategy that would be Vyāsantōḷ’s undoing—prove that Vyāsa’s arm is not a “religious” feature of the Nandikamba procession and that non-religious processions are not protected under the law. A series of cases in the 1930s and 1940s did precisely this.

In the early 1930s, the Sub-Divisional Magistrate of Bijapur prohibited Lingayats in the small village of Mangoli from conducting a Vyāsantōḷ procession. In the process of hearing the Lingayats’ lawsuit against the magistrate’s decision, a lower appellate court determined that Vyāsantōḷ was not a “religious” rite on the grounds that it had not been “enjoined or even recommended by any shastra or work containing the tenets of the Lingayats or the Veershaiva faith.”64 In other words, Vyāsantōḷ lacked the kind of scriptural and scholastic edifice that propped up many Brahmanical rituals. This extraordinarily narrow definition of a “religious procession” was upheld by the Bombay High Court in 1945, after the Mangoli case had bounced around in lower courts for more than a decade.

The 1945 case is significant not only because it determined that Vyāsantōḷ was not properly religious and was thus not protected under the law; it also appears to have been the first time a plaintiff argued for a general non-religious right to procession. Drawing on a series of rulings concerning the Shi’i Matam procession, the lawyer arguing the Lingayats’ case in 1945 claimed that the law protects a general right to procession.65 The Bombay High Court disagreed, but three years later, while hearing a lawsuit that sought to prevent a procession during the Dasara festival from passing by a mosque in Sakur, Maharashtra, the Bombay High Court reversed their position and determined that the law protects a general right to procession. In their decision the judges wryly asked, “can it be said that conducting a non-religious procession along a thoroughfare is a less lawful and reasonable use of a highway than conducting a religious procession?”66 Too late. By 1948, the litigious zeal of Lingayats in the Deccan appears to have dissipated, or at least the practice seems to have no longer been litigated.

In deciding that texts make a rite or ritual “religious,” the courts tilted the tables toward Brahman religiosity and away from oral and non-textual forms of devotion. This is not an unfamiliar story: historians have long pointed to the outsized power of Brahman pandits in colonial jurisprudence. But Vyāsantōḷ is not simply a story of Brahman triumph over lay religiosity. The circuitous path the practice took through colonial courts highlights decisions on the part of the judiciary to protect (at least for a time) certain practices that Brahman communities vigorously opposed. Vyāsantōḷ’s public life many have ended when the judge’s gavel dropped in Bombay in 1945, but the practice has much to tell us about religious conflict in the subcontinent and their textual pre-histories.

Thanks are due to Elisa Freschi, J. Barton Scott, Andrew Ollett and the anonymous reviewers, whose comments and insights on various drafts proved most crucial.

Notes

-

↑Wodeyar’s dispensation was found in the library of the Sringeri Śāṅkara maṭha at Koodli (near Channagiri) in 1945. Collectors deduced that Wodeyar sent a copy of the decree to Brahmans at the maṭha because they petitioned the court to intervene in the procession. Doing so may have endeared Wodeyar to the region’s Mādhva and Smārta Brahmans at a moment when their support was vital to securing Mysore’s power over western Karnataka. It is unclear whether a copy of the document was also sent to the Akṣobhyatīrtha Mādhva maṭha in Koodli. See sannad no. 3 in the “Sannads of the Mysore King Mummadi Krishnaraja Wodeyar,” in Annual Report (1946).

-

↑Elsewhere, Vādirāja writes that Buddhists, Jains, and Vīraśaivas—the pāṣaṇḍas—once accepted, but ultimately rejected, the authority of the Vedas. “Apostate” is closer to this understanding than the more commonly translated “heretic.” See Peterson (2023).

-

↑See Jesse Pruitt’s forthcoming work on the Śivadharmōttara.

-

↑Later Purāṇas speak of as many as eighteen Vyāsas. See Viṣṇupurāṇa 3.3.9 (ed. Sampatkumārācārya 1972: 191).

-

↑The figure of Vyāsa has accumulated a considerable scholarship. A study of his divinization alone would include Shembavnekar (1947), who showed that “Vyāsa had nothing to do with the four Vedas.” It would include volumes written about Vyāsa in the field of Mahābhārata studies, such as Sullivan (1999) and also studies on specific chapters and sections of the Mahābhārata. Grünendahl (1989 and 2002, and Grünendahl and Schreiner 1997) for instance, describes how Vyāsa became an “emanation of Nārāyaṇa,” and the scholarship of Biardeau (2002), Hiltebeitel (2005), and others has convincingly shown the Nārāyaṇīyaparvan to be a later feature of the epic and to reflect the interests of new cults of Viṣṇu worship in the first centuries CE . Such a study would also include work on Vyāsa in the Purāṇas, like Saindon (2004–2005) and Bisschop (2021).

-

↑See Madhva’s Mahābhāratatātparyanirṇaya (ed. Gōvindācārya), v. 2.41, and Mahābhārata 12.334.9 (ed. Sukthankar and Belvalkar):

kr̥ṣṇadvaipāyanaṁ vyāsaṁ viddhi nārāyaṇaṁ prabhum -

↑Madhva says the verse is from the Bhaviṣyatparvan of the Harivaṁśa, but it is probably one of his own compositions. For more on Madhva’s untraceable sources, see Mesquita (2000, 2008).

-

↑Concealed from ordinary people during the Kali Age, Vyāsa nevertheless welcomes Madhva’s mind and eyes (cetōnayanābhinandana). Nārāyaṇa likens Vyāsa’s disappearance from the vision of ordinary people in the Kali Age to the disappearance of the sun at night (Nārāyaṇa Paṇḍita, Śrīmadhvavijaya [ed. Gōvindācārya] v. 7.22).:

adhunā kalikālavr̥ttayē savitēva kṣaṇadānuvr̥ttayējanadr̥gviṣayatvam atyajad bhagavān āśramam āvasann imam -

↑Nārāyaṇa Paṇḍita, Śrīmadhvavijaya (ed. Gōvindācārya v. 7.17):

nijahr̥tkamalē ’tinirmalē satataṁ sādhu niśāmayann apiavalōkya punaḥ punar navaṁ tam asau vismita ity acintayat -

↑The verb śritavantaḥ in verse 27 conveys that the toenails are both connected to and have taken refuge at Viṣṇu’s feet, much as a disciple might. The suggestion seems to be that just as the toenails remove darkness and surpass the sunrise in their splendor, so too the disciple—in this case, Madhva—can do the same.

-

ucitāṁ gurutāṁ dadhat kramāc chuci tējasvi suvr̥ttam uttamambhajatō ’tra ca bhājayaty adō vibhujaṅghayugalaṁ sarūpatām

“The Lord’s two legs, appearing fittingly burly from bottom to top, are pure, brilliant, well-made, and excellent. They cause the person who worships him to become the same/to attain mōkṣa.” The pun here is on sarūpatā being a stage of mōkṣa, on which reading the legs confer the appropriate gurutā according to one’s stage of enlightenment (cf. Br̥hadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 5.13.1–4 [ed. Limaye and Vadekar 1958: 262–263], which is echoed later in the Bhāgavatapurāṇa and elsewhere).

-

acalāsanayōgapaṭṭikā varakakṣyā sakr̥dāptam iṣṭadamparitō ’pi hariṁ sphuranty ahō aniśaṁ dhanyatamēti mē matiḥrucirēṇa varēṇa carmaṇā rucirājadyuticārurōciṣāparamōrunitambasaṅginā paramāścaryatayā virājyatē